On Charles Irvin

“For a brief green flash, we all get to feel the possibility of another, parallel world.”

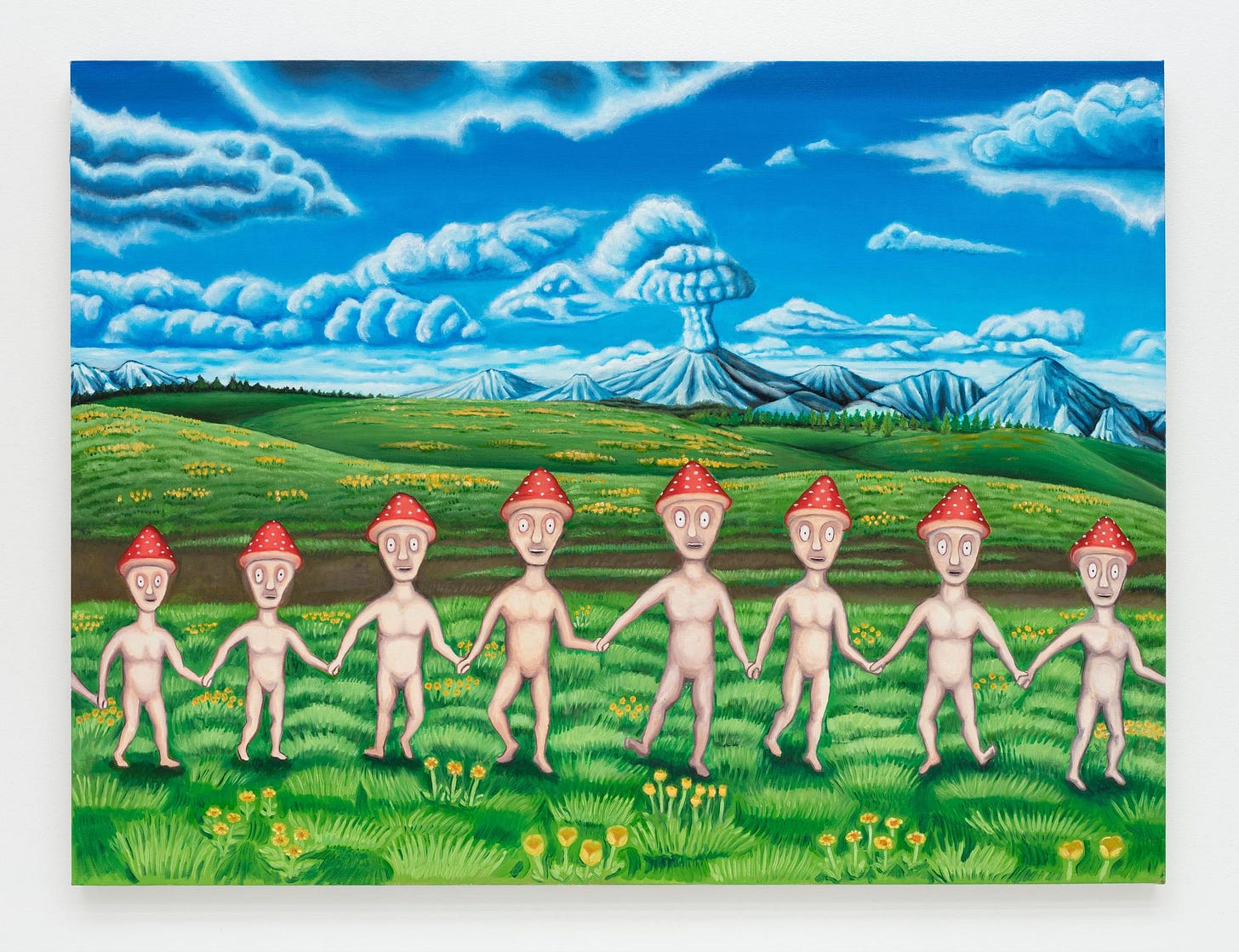

Worldbuilding began as a literary device. Writers invent flora, fauna, new modes of transportation, and entire human races to arrive at another plausible reality. Oftentimes, these worlds are proximate to our own, as if over the next hill, strange, unknowable encounters are ever possible. It’s this uncanny nearness that can make such worlds all the more affecting to enter.

Less often are painters called world builders, though there are many who have set out such a task and succeeded. M.C. Escher. Leonora Carrington. Remedios Varo. Hieronymus Bosch. Unlike fantasy literature or science fiction films, there aren’t usually names for the elements of a painter’s world, which makes it all the more disorienting and intuitive. Only vision can access this plane of existence.

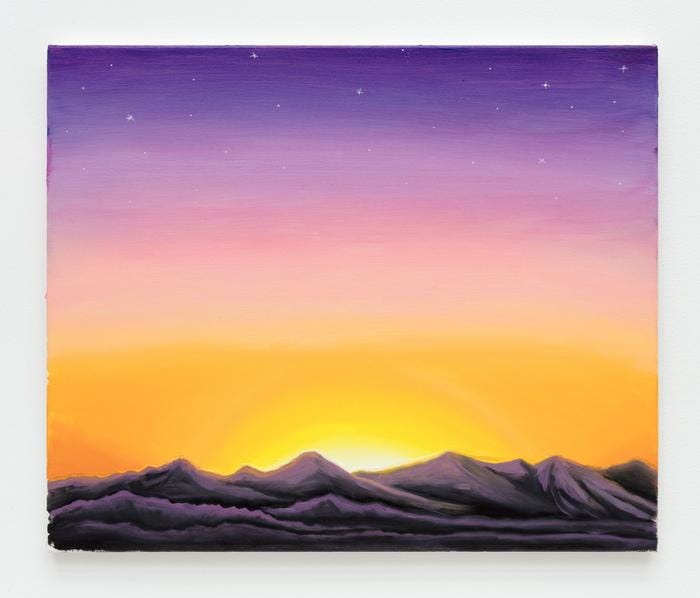

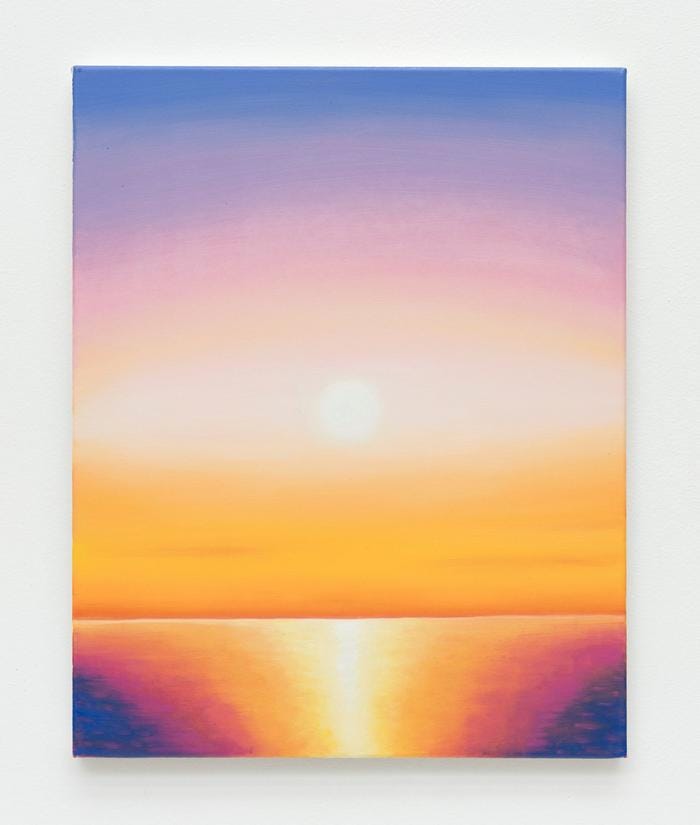

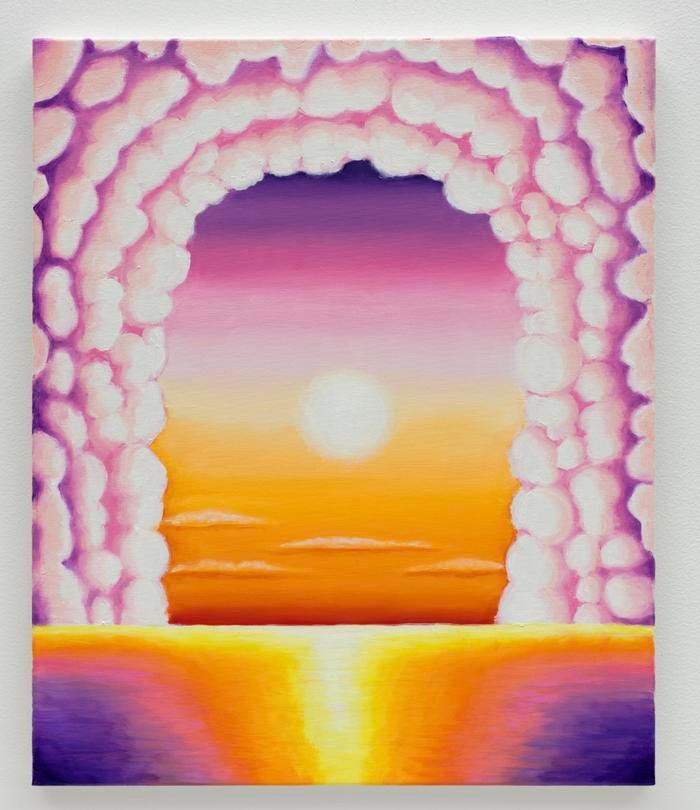

The work of Charles Irvin gently presents a striking new world to the viewer in celestial blues and creamy browns. At first glance Irvin World seems like a pleasant place, mostly consisting of mountains, oceans and sunsets— classic subjects for a painter — but these landscapes are alien, and the beings who live there are not part of any terrestrial mythology. Here, the light almost looks like our own, and yet its beams seem to strike our eyes with a kind of unfamiliar brilliance, making the viewer a little unsteady and heightening our awareness with the subtle threat of the unknown.

Irvin’s reality is not a perceived reality but an imaginal one. His landscapes are closer to the curious child’s than the plein air painter who copies what their eye can see. When young children paint a mountain, they do not concern themselves with the actual grey mountains out their window; they paint their own, personal mountain. They are building their inner world.

Philosophers, too, can be world builders, but instead of narrative or image, they use raw language. The esoteric philosophers of the early 20th century seem especially willing to create world systems that encompass every aspect of life, from the mundane to the mystical. Rudolph Steiner, Madam Blavatsky, and Emmanuelle Swedenborg all built worlds that continue to live on in the minds of their readers.

The philosopher and composer, G.I. Gurdjieff created a particularly vast cosmology — “ray of creation” he called it — in which he diagramed the whole spectrum of the universe as a musical scale, with each element resonating at its own Pythagorean-esque frequency. The sun, the milky way and the absolute (which, Gurdjieff made clear, is not “God”) all vibrate uniquely.

Irvin’s work thrums at each of these levels, marveling at the vast panorama of the heavens. Like J.M Turner or Carl Sagan, his work is to cultivate a desire for the yawning chasm above us, to remind us all to look up. He wants to experience mystery in the way humans have done since our arrival on this planet, which in Gurdjieff’s parlance is called Mixtus Orbis: the earthy, vibratory reality we all experience daily.

Irvinverse is often framed by Mixtus Orbis, perhaps a craggy, barren expanse or a sparkling sea. But this is not a real desert or a literal ocean. This stripe of land or water is here to provide a contrast to infinite above. At times, it could be a grounding mechanism, to keep the picture and its maker from floating off into pure ether, but usually, this is an airstrip, a runway for projecting our eyes up and into space.

That’s what these paintings are — portals into celestial imagination. This is why Irvin (and every other human being) loves sunrises and sunsets —they, too, are portals. They open twice a day and allow us to pause, and behold the meeting of two realities: day and night. For a brief green flash, we all get to feel the possibility of another, parallel world. With his brush, Irvin freezes us in that hypnotic moment. He tilts our head back, carves the clouds into the arc of a doorway, and places a humming sun between our eyes, beckoning us to step across the threshold.