Field of Pain

On Matthew Barney and Failure

When I first became addicted to aspiration, I began to fear failure. This was especially true for making art. When I started aiming for greatness, I wanted a direct path to my goal and considered any deviation a mistake. This desire made for a painful process, but it’s the game you play when you play with ambition; suffer in the face of this chaotic reality or find energy within the failure that is inevitably, relentlessly to come.

I heard about Matthew Barney’s work before I saw it in person. Among young artists I knew, he was spoken of as symbol of greatness. He made big sculpture, epic films, and athletic performances. I first saw him on a 2001 episode of Art21, an American documentary series on contemporary art. There, Barney’s father talked about his son’s early interest in becoming a plastic surgeon. He said, “[Matthew] just goes out and does things. I don’t know what it is… he doesn’t seem to have the fears that the rest of us do. He just seems to go straight at it and find a way to do it.”

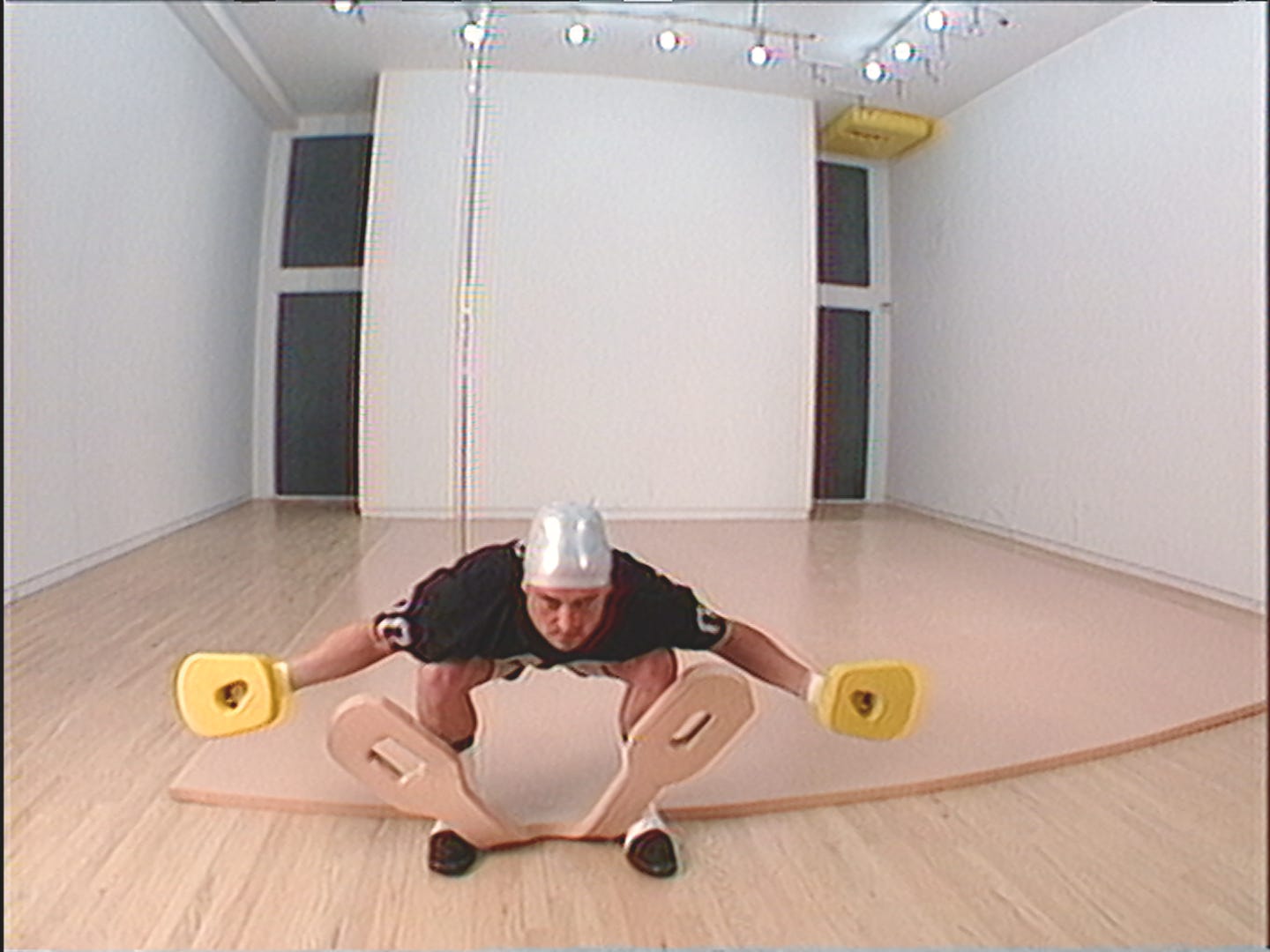

My first physical encounter came a few years later, with Drawing Restraint 14 (2006) at my hometown museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. This was part of a retrospective of Barney’s multimedia Drawing Restraint series (1987- present), many of the components of which involve him pulling, leaping, lifting or dragging while attempting to draw. The finished product is usually tentative, smeared and strained marks. Like many goal-addicted artists, Barney seemed to be inventing absurd obstacles for himself, to manufacture the pleasure of achievement.

In the silo-size stairwell at SFMOMA, he had climbed the side of the building’s fifth storey to make a faint technical diagram, surrounded by the scuffs of his loafers and centred on his ‘field’ symbol – a pill or stadium shape with a line across it. This is Barney’s logo, which he has applied to everything he makes, from his earliest works to his newest film, Secondary (2023). For him, this altered crucifix represents a body (pill) against a restraint (line) – an illustration of the fundamental situation of his work.

The remains of this ‘action’ – a term that recalls Joseph Beuys, film directing and Arnold Schwarzenegger – hummed with the haunted atmosphere of a crime scene. What I felt there, and what I continue to feel in Barney’s work 17 years later, is the seedy, embarrassing desire of ambition, followed closely by its shadow: the ominous threat of defeat. In the work, I could also see that Barney was willing to destroy his art as he made it. He was rough it, even violent, forcing the work to be robust, unlike so much art that insists on its own preciousness to demonstrate its value.

I often think about Barney’s work through writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s philosophy of antifragility, within which stress improves a system, a person or even an artwork. Or perhaps a more relevant concept is hormesis, through which small damages to a body improves its function. Weightlifting, for example, is a process of creating tears in muscles so that the tissue will grow stronger when it heals. This is known as hypertrophy, a concept that Barney began working with in his Drawing Restraint works, made while a student at Yale.

And just as a bodybuilder pushes their calves to point of fatigue, many of Barney’s sculptures push materials – lead, bentonite, zinc, self-lubricating plastic – to point of failure. Occidental Restraint (2005), a roomsize installation of collapsed industrial plastic, is the result of Barney’s attempt to make a cast of a purposely excessive amount of an unstable material.

Secondary takes on failure at the thematic level. It is a cinematic tone-poem on the crisis of American football, told through dance, chamber music and true horror. (‘Secondary’ refers to a defensive position group on a football team.) The film considers the game of football’s willful destruction of human bodies for capital and entertainment, a problem that has become increasingly glaring in recent years, as the longterm effects of repetitive concussions become more apparent.

The film runs at an hour (same as a football game), which is significantly shorter than Barney’s past work. It’s also more modest in its production (sets, costumes, locations) than his previous films, which have, for the most part, grown in ambition over the past three decades. Rather than take on the mythological scale of most of that work – with characters and stories from Egyptian, Greek, and Japanese myths – the entire film is the investigation of a single historic moment.

Where Drawing Restraint focuses our attention on overcoming physical challenges, Secondary is an expression of pain without transcendence. It retells an American tragedy: in 1978, Jack Tatum, a safety (part of the ‘secondary’), slammed so forcefully into Darryl Stingley on the field that he snapped Stingley’s spinal cord, paralysing him at age twenty-six.

Barney viewed this event on television as a young man but went on to play football anyway, first in high school and then at Yale. But in college he quickly turned to art instead. (Recently, Barney has said he’s glad he stopped playing when he did, for the sake of his body.) Yet football remained on his mind, and he returned to it often in his work. Sometimes this was direct – the setting of a stadium, the use of players as characters – and sometimes it was indirect, such as his sculptures made with the polymers used in protective football equipment and the petroleum jelly slathered on the athlete’s body.

While many professions negotiate failure and success, few are more explicit about it than the professional athlete – every game is an unequivocal win or loss. ‘I came of age on the football field,’ Barney told Art News in 1993. ‘That’s where I started to construct meaning in my life, as an athlete. I think athletes are people who understand things through their bodies.’

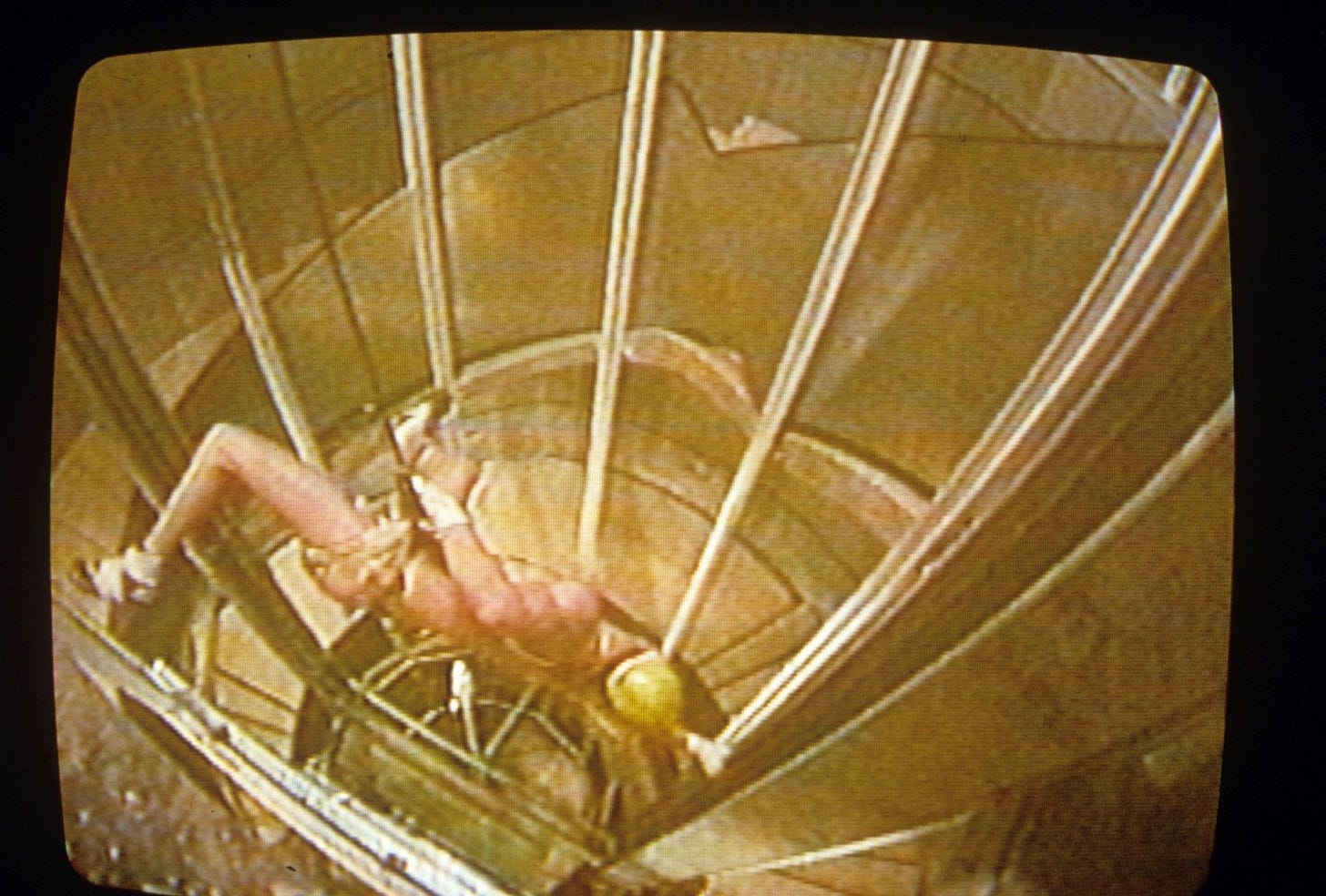

Like his early videowork Repressia (1991), Secondary was screened in the same place it was shot – in this case, Barney’s Long Island City warehouse-studio, right before he closed it down and moved to another location. To experience the five-screen, surround-sound installation, hung like a Jumbotron, I sat on the same Astroturf on which the actors and dancers had performed. On it was printed a beam of light refracting through Barney’s field symbol, an image that was also repeated multiple times throughout the film and studio, echoing Drawing Restraint.

Throughout Secondary Barney recapitulates ideas from his previous work. In my single viewing I picked up on elements of the video-sculptural works, The Jim Otto Suite (1991–92), The Cremaster Cycle (1994–2002) and River of Fundament (2014) – titles that gleam with the sharp vocabulary of death metal. One of my favourite self-references is the oversize game clock that Barney installed for the film on the facade of the studio, hanging above the East River. Throughout the film, the clock counts down until it begins relentlessly flashing ‘00:00’ with the apocalyptic finality of broken time. While these numbers refer to the end of the game, they also recall the double zeros worn by football player Jim Otto, who endured famous levels of sport-induced damage and prosthetic repair – supposedly 78 operations. During the 1990s, when Barney employed Otto as a character in his work OTTOShaft, he considered these ‘0’s as a ‘twin roving rectum’ on the field. This knowledge transforms those clock digits into a quartet of anuses blinking onto the surface of the faeces-infected river – which was, incidentally, a central character in River of Fundament.

From 2012 to 2013, I spent many of my days on the set of River of Fundament, a vast operatic project that included a five-hour film, live performances and a fleet of automobile scaled sculptures. It is by many measures his most ambitious work so far – in length, production value, personnel. I was working on an essay about the project’s music (composed by Barney’s longtime collaborator Jonathan Bepler), which would appear in the River of Fundament monograph. I also planned to write a book on the making of the film and spent hours interviewing and notetaking to this end.

The project was an adaptation of Norman Mailer’s big historical saga Ancient Evenings (1983), a surreal, modernist retelling of Egyptian mythology that seemed to resist any traditional approach adaptation. Mailer had asked Barney to adapt the book shortly before his death, probably because he knew it was a towering challenge that no-one but Barney would consider. The film included Hollywood actors (Maggie Gyllenhaal, Ellen Burstyn), musicians (Debbie Harry, Milford Graves) and other cultural luminaries (Fran Lebowitz, Dick Cavett). It was shot at several locations around the United States, including Barney’s studio, where the artist rebuilt Mailer’s three-storey apartment. Unlike previous films, which had been made in private, Barney created a series of largescale, semipublic performances as sequences in the film. At one of these he performed what he said was ‘the largest nonindustrial iron pour that’s ever been attempted’.

I attended several of these performances (and appear as a bystander in one of them) and ended up publishing several essays on the whole production for various art magazines. But I failed to reach my intention to write something longer. Though I found the work to be a striking success – as music, film, performance and sculpture – I just couldn’t seem to get my head around it. The whole thing was too multifarious, too ambitious in scope to be compressed into explanation.

This is true of many Barney narratives, which fail to come together in any reducible way. For me, this is often the work’s purpose. I love how the films refuse clear forms. As a story they don't seem to require cause and effect to be pleasurable, even at long stretches of silent action. This is true for many works of art, but Barney’s use of cinema and myth seems to encourage viewers to look for a kind of cohesion that, thankfully, never arrives. For me, the work remains a mystery, and I would like to keep it that way.

What often ties Barney’s work together is an atmosphere of pain. Bepler’s music plays an important role in stimulating this dread – hoarse winds, extended vocal techniques, unexpected arrangements. As in horror films, this is the sound when someone is about to get hurt. Pain is a kind of physical failure, and Barney often focuses on the self-imposed kind of pain. The two recurring figures in his early work – Harry Houdini and Otto – were extreme examples of people who chose a life rubbing against their body’s limitations.

In Secondary, Barney plays the character of Oakland Raiders quarterback (Barney’s position in school) Ken Stabler, who was diagnosed after death (he died, aged sixty-nine, in 2015) with chronic traumatic encephalopathy from the many hits he endured. In this role, Barney’s body becomes the site of suffering and humiliation, as it often is in his films. While other characters dance gracefully, Barney straps the inside guts of the football helmet to his head, willingly allows his coach to pour molten metal onto his skull and tries but repeatedly fails to run his plays.

Over and over he falls, smacking down hard onto concrete, flat on his back, actively damaging his body on camera. (Barney trained to avoid serious injury.) It’s tragic, but also funny in a Chaplin slapstick way. This is a black comedy of errors. Nothing good comes from the events in this film.

And yet, it’s when the terrible act of violence happens in Secondary that something strikingly beautiful comes into being. Barney’s work always, in some way, tells the story of making sculpture, and in Secondary this occurs when Stingily and Tatum collide. In this moment, they produce castings between their chests, like two hands pressing together clay, capturing the force in a physical object. Initially, these alien forms appear from nowhere and fall from between the two men, bouncing and jiggling like fat tissue, but the final casting, made of terracotta, hits the floor and shatters like Stingley’s vertebrae. In this single gesture, Barney’s transforms a great and terrible accident into a source of creation. Nothing has been redeemed, but in that moment something new was irreparably conceived.