The philosophy of vitalism describes a mysterious force of life circulating within every object in the world. For centuries, science has been doing its best to reduce life to a purely biological process, but ancient strains of thought — what we now call animism, panpsychism, vital materialism— have long attributed life to all manner of things, from monkeys to litter, plastic to rocks. Consider a mountain as an expression of the earth’s desire — in its mountainous form, its tawny color, its dynamic presence. The neo-vitalist philosopher, Jane Bennett even considers humans “walking and talking stones,” since life itself erupts from the bubbling magma at the center of the earth.

The work of Daisy Sheff makes visible the power of the élan vital, or vital force, a kind of background radiation, which vibrates behind our reality. It’s in the sea, the sky, the pages of books, the walls of our homes.

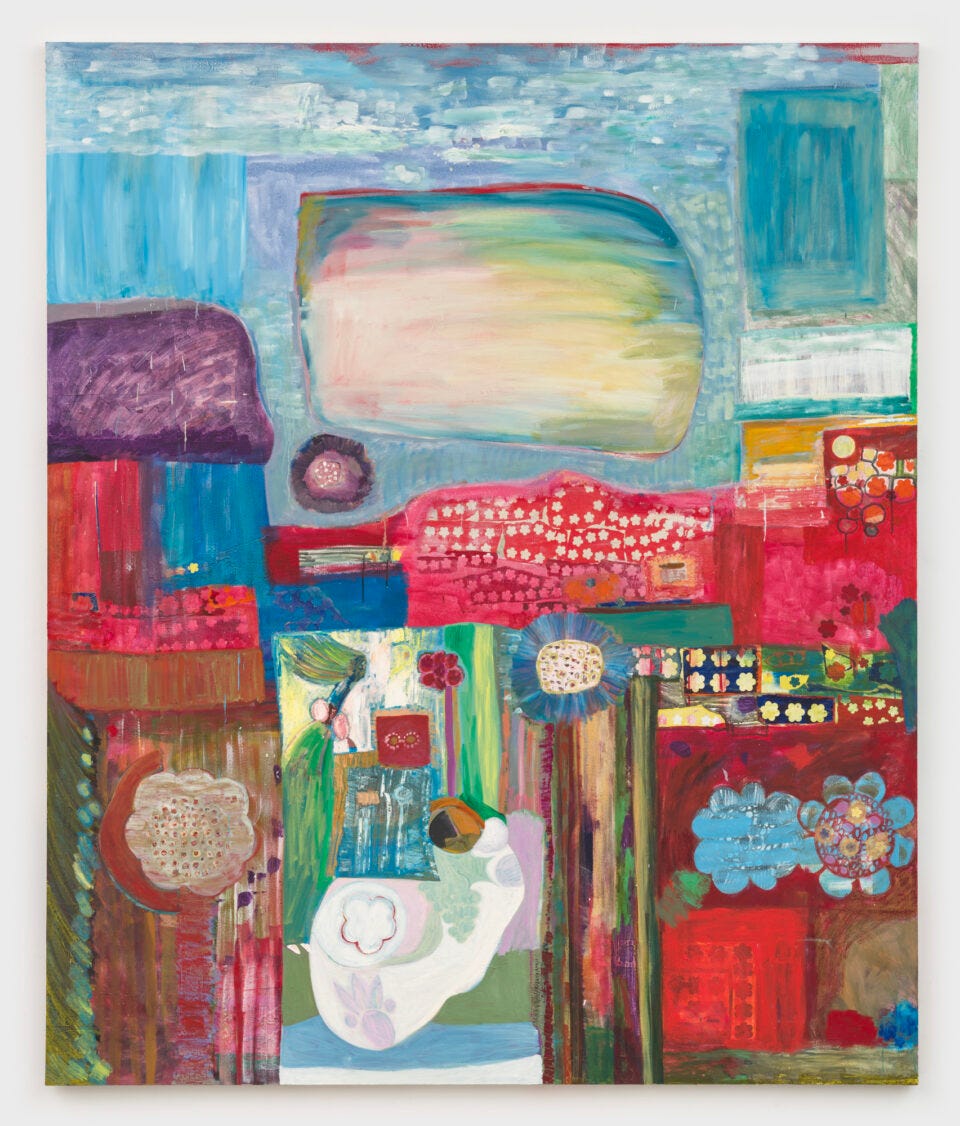

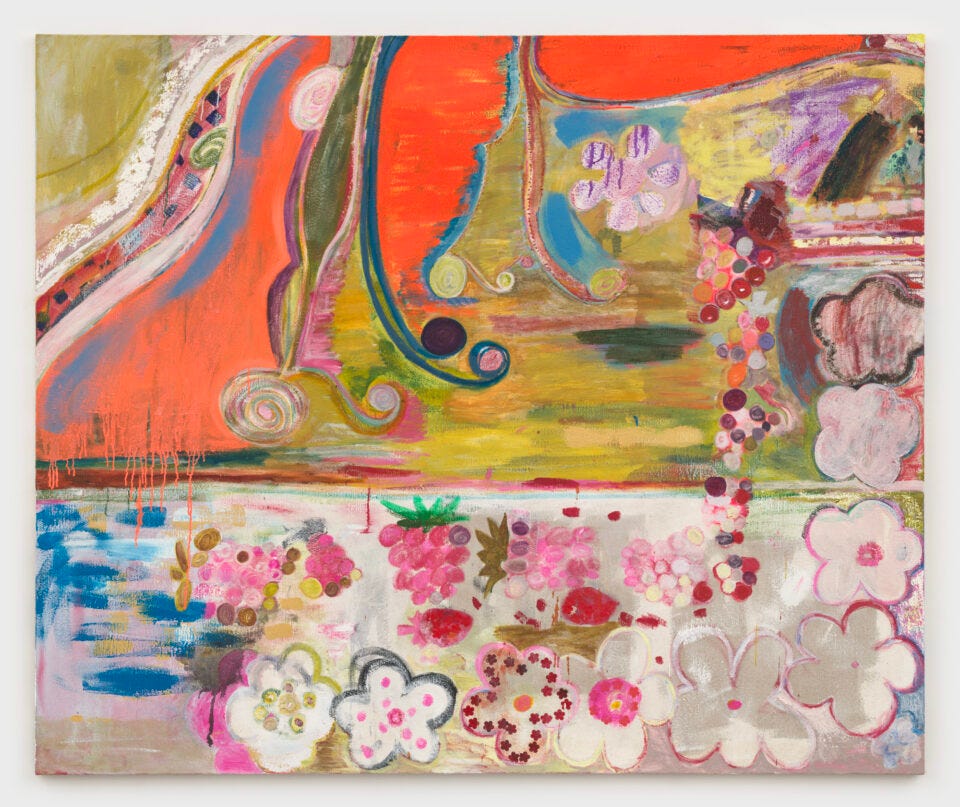

In Sheff’s work, we watch as butterflies, piebalds, berries and barnacles all sprout from infinite fields of color. Natural and artificial hues fill canvases like seaside fog. Figures become haystacks becoming waterfalls and they wear garments made of meadows bedecked with flowers, rolling into the decorative patterns of kitchen towels — everything growing and weaving together like a single tapestry, free of difference, full of narrative.

Sheff recently sent me two quotes from Blindness, a novel by Henry Green.

“The dew has made a spangled dress for everyone.”

And

“When the sun sucks up the dew and the moistness of the gossamer, everyone will be for himself again.”

These lines draw our attention to the marvelous glinting sheet of water that settles across the world every morning. Picture a thin veil of dew glistening atop a disposable bottle of water lying on the side of the road. The potential for life is everywhere.

Sheff is a joyful reader and literature forms her visual perception. Sometimes she works amidst the sonic atmosphere of audiobooks. She depicts physical tomes, references their stories, invokes them in titles, and paints metaphors, conjoining multiple images within a single canvas.

She also sent me a quote from the novel, Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner, an intimate encounter with dark magic that Sheff refers to as her “bible.”

“When Mrs. Leak smoothed her apron, the shadow solemnified the gesture as though she were molding a universe. Laura’s nose and chin were defined as sharply as the peaks of a holly leaf.”

Like this, Warner assembles characters from earthen elements and conjures imaginal landscapes drizzled with paganism, places just across the valley from the rainbow swamp of Sheff’s work. For me, both these artists’ realms cultivate the feeling of possibility, a sense that, at any moment, the evening wind might call me to enter the unknown.

With a tone of omniscience, Sheff considers how much she plans to “animate” her characters and ecosystems for each painting, as if she’s doling out lifeforce in brushstrokes. Through painting, she manifests her wish that “mysterious tiny figures might exist” and depicts her daydream of “sleeping in a flower.”

Through one painting, she invokes a Grimm’s fairy tale, in which characters bring a “sea grub sausage” to life, watching as it “takes wing and bursts from a cauldron.” Merpeople and fair folk are as common here as human beings.

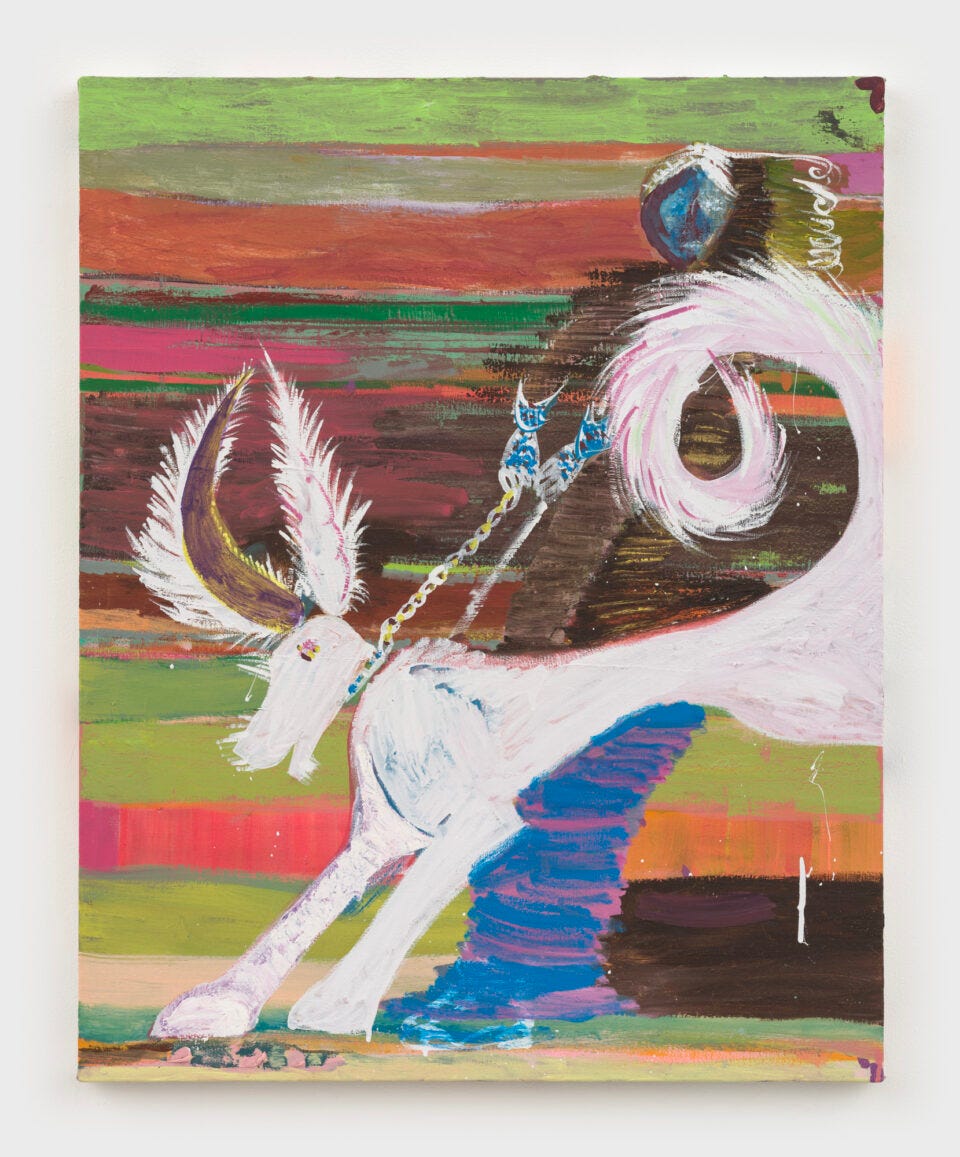

Such a playful relationship with the substance of life comes out of Sheff’s lived experience. She is a surfer, with a lifelong relationship to the ocean, a supposedly inanimate entity that, nevertheless, expresses as much life as it contains. She holds an ongoing “fantasy of being alone on a beach with the ocean,” as if the sea were a romantic partner with whom she longs to truly know.

Another primary relationship in Sheff's life is with Blinky, her dog, named after the artist, Blinky Palermo. This is an animal who teems with life force, tearing across landscapes, flinging his 100 lbs into the chests of visitors, and napping beside Sheff as she paints in her living room. Blinky’s exuberance demands a place at the center of Sheff’s life, and so, he often appears in her sculptures and paintings, standing at attention, with arms outstretched in the embrace of love.

Anyone who has fallen in love with an animal knows how an intimate, trans-species relationship can redefine one’s entire boundaries of life. In the face of pet-love, the priority of human connection wavers, and soon, the whole accepted hierarchy of human-animal-plant-mineral dissolves, leaving us with a newborn reverence for all things great and small. The fly on the windowsill is now filled with fresh agency, as are the clouds above it, like floating, benevolent sheep. The sun becomes God; the ground becomes mother, and the nylon-bristled paintbrush suddenly hums with it all.