1

A video for my song "Can't Stop Me" off the album, Refrains is up now on youtube and features footage from my 2020 performance in Armstrong Woods in Guerneville, where I was then living. It was filmed by Jeremy Greene with a drone. You can see further documentation of my annual mud performances here. You can also find the music on Spotify and Bandcamp.

2

The next exhibition at Alicia will be this coming Sunday at 11am - 2pst and will feature the artists Ashley Carter, Celia Hollander, and Marisa Takal. It will include a performance by Celia Hollander, a breakfast by Marisa Takal, and archery lessons by our neighbor, Star. If you’d like to come, drop me an email for the address.

3

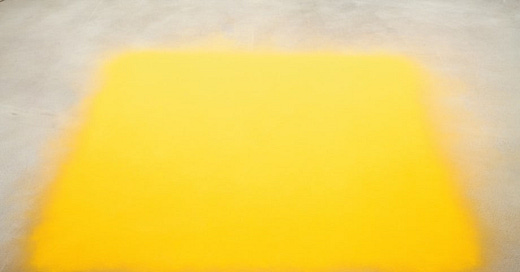

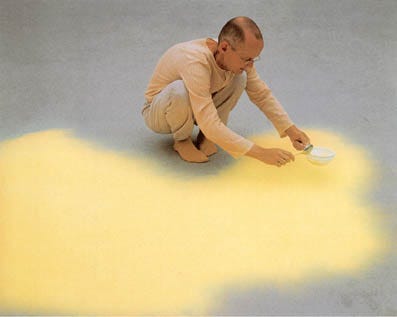

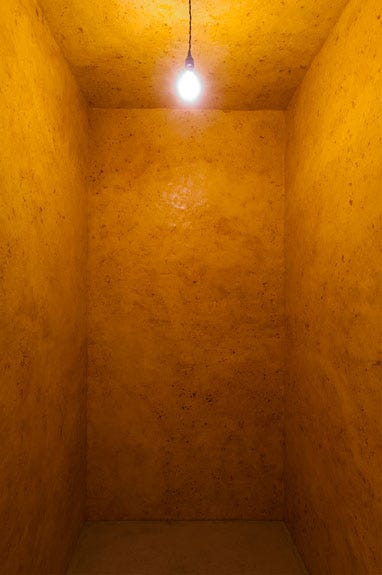

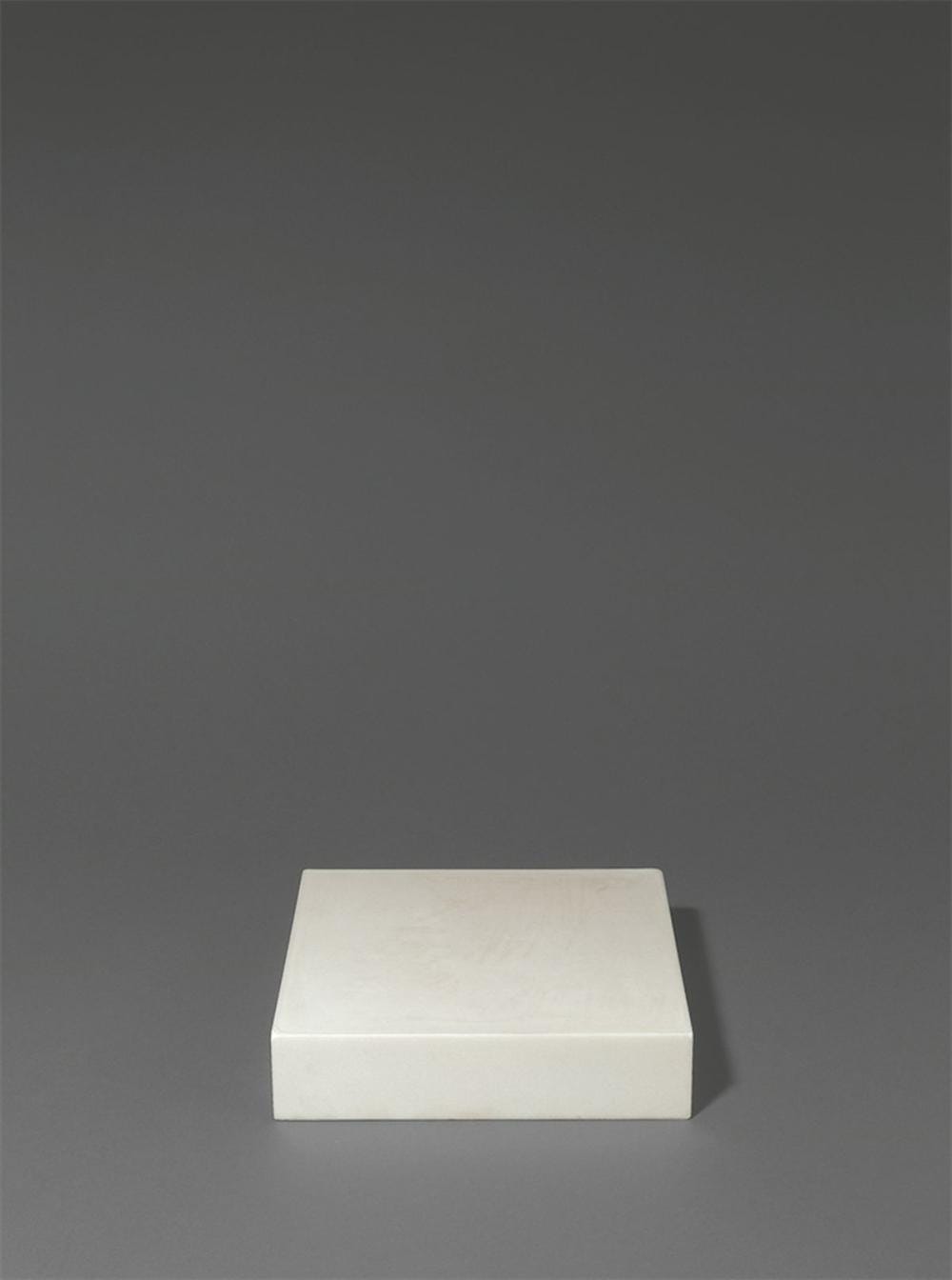

An interview with Wolfgang Laib

Wolfgang Laib's sculptural materials include beeswax, pollen, stone, milk, and rice. With beeswax, he builds towering ziggurat sculptures and wax covered caves, such as the one he created on his own property. Pollen, on the other hand, is available in only small amounts, and he collects it over many years from the bushes and wildflower fields surrounding his exquisite German home.

Laib's work emits a subtle energetic resonance, as does Laib himself, who speaks with monastic restraint. In addition to his family's home in Germany, he divides his time between an apartment in Manhattan and a small village in India.

Laib and I met in the atrium at the MOMA, where his largest hazelnut pollen installation was then installed. He continued to maintain and clean the pollen every few days until the exhibition closed, at which point he recycled the pollen into his next installation.

RS: How did you become an artist?

WOLFGANG LAIB: I began to study medicine, and then after, I was very dissatisfied with everything, and I felt before that art is something very important, but then the more I went into the world, the more I felt that art is the most important thing in the world, and therefore I became an artist.

ROSS SIMONINI: Why did you think art was the most important thing in the world?

LAIB: Because, somehow, it includes everything. And everything else, like medicine is a natural science, or a politician has to do a certain thing, but art is something which is so open, and has all the potentials. It’s not a science. I think science can be incredibly good, but I felt it’s always very narrow. Where I felt that art is something very open and very universal.

SIMONINI: Do you think it’s always been that way?

LAIB: I think it’s worse than before. Because I think our art world can be very, very narrow. Very disappointing. I think in all the centuries there was always something very exceptional, and there was many who just made what everybody else did. And I think that happens now, exactly the same. And these things become very narrow.

SIMONINI: Do you think you would have been an artist in previous centuries, too? Your artwork, as it is now, probably wouldn’t have been considered art.

LAIB: I would believe that I could have done a pollen piece 2000 years ago, and 2000 years from now. And that is not modest, what I say, but I feel that it is something very important. That art is not something that is like a fashion.

SIMONINI: Timeless?

LAIB: Yes. I feel much more close to art which happened 2000 years ago in Asia, or in Africa, or wherever. I think we came to the point where every other year, or every other week, something has to happen. But that’s a disaster. And somehow, I feel the opposite. I feel like when I go to the Metropolitan Museum, I feel very close to something 2000 years old. And that’s something very beautiful. Like Egyptian art, or a Mesopotamian art, or something which is very far from our own culture, but which is a challenge to our own thoughts, and our own thinking.

SIMONINI: Do you think this work has been important to you because it’s distant from you in time, and place? Or it would have been important at the time, too?

LAIB: Both.

SIMONINI: So you feel that this historical work was superior to contemporary art?

LAIB: Yes, that’s what I’m saying.

SIMONINI: Is there any artwork today that you find to be compelling in this way?

LAIB: I realize that so many artists now, and people always ask me, there are so many artists now who make art from other artists. Of course, if you live in such a big city, as here, and every day you see all these things, I wouldn’t know, anymore, what to do. Because you’re so influenced by everything you see. And of course, many artists like this. But for me, I think it’s the opposite. I live in a very small village, and I work there, totally alone, and somehow, for me, this work came out of my own life, and out of my own inside, and not from the outside. I see that here, when I look at galleries, there is so much art made from other art. And not from the inside.

SIMONINI: Are you not making art from other art? From the past? Even Egyptian Art?

LAIB: No. Of course, you can, say, from the outside, an art historian can say, this has a relationship to this, and this to Joseph Beuys or something which is most probably correct, but from my side, it’s very important to create something out of your inner self.

SIMONINI: Do you feel any connection to Germany? You say that your work comes out of a local village. Do you not feel any connection with the Germanic tradition?

LAIB: No. I think the Germans, they don’t want to be German at all. [Laughs] But when you see it from the outside, I think there is a very long tradition of German philosophy, and German thought– I would maybe say, middle Europe– which has this kind of thought and philosophies, which I am very close to.

SIMONINI: Who is that? Schopenhauer?

LAIB: Schopenhauer, yes. Nietzsche.

SIMONINI: How do you feel close to their thinking?

LAIB: I find Nietzsche very good. Because he’s very challenging, and sometimes impossible, totally ridiculous and awful. But I think there is nowhere else in the world somebody who thought like that. And somehow to make a pollen piece, or a milkstone, has to do with this.

SIMONINI: Would you be able to describe this middle European thought?

LAIB: Somehow searching for the essence of life, or our existence.

SIMONINI: Is your work a philosophy?

LAIB: I mean, you could see a pollen piece and you could see a visual experience. It’s an incredible color, like you can’t see anywhere else, but if art would be only a visual thing, or a color, or a pigment, I wouldn’t be an artist. I wouldn’t want to be an artist.

SIMONINI: But at the same time, you seem sort of resistant to talking about your art in terms of the thought behind it–

LAIB: I want to leave it open. Therefore I would never give a really honest talk. It’s also not very important what I feel is behind the work, it is what it is. It’s not even important what I have to say about it. It’s important that I put it into this context, into the art world. A milkstone is not a white painting, and a pollen field is not a yellow painting, like Rothko’s. It’s something much, much more. And it’s also not a blue painting. It’s like the blue sky.

SIMONINI: Do you have a resistance to language?

LAIB: No, I think from the artist’s side, if I were to say too much, but from the outside, there can be–

SIMONINI: Lots of language?

LAIB: Yes.

SIMONINI: That doesn’t bother you?

LAIB: Not at all.

SIMONINI: Okay. Is there such a thing as a misrepresentation or a misreading of your work?

LAIB: I mean, it is, of course, such a simple work, and you have to go with it, see what people say. It’s amazing. When I stand there for ten minutes– there’s so many emotions, so many reactions. People bring their own thoughts and meet something else. Many things happen. And that’s very, very beautiful. And it doesn’t matter. I wouldn’t say it’s a misinterpretation, because there’s all sorts of things happening. So somebody feels this, the other one feels this, and the other one is challenged, or says ‘it’s something I’ve never seen before in my life.’ I was in another museum this morning, and a young woman came to me, and said to me very shyly, ‘Are you the artist of the pollen piece? I’m going there every day. I’m going there every day and it makes me so happy. It’s such an incredible experience I’ve never had in my life.’ And that happens. It’s unbelievable. That doesn’t happen so easily in front of a painting. You love a painting, or you find a good painting, but I know that from other exhibitions the pollen piece or the milk piece has incredible emotions. Like, people weeping.

SIMONINI: Do you ever have these experiences when you look at the work?

LAIB: For me, I feel like its part of my life, it’s my life. To see the pollen piece, I don’t have something else. That’s my inner life. My life is my work. I don’t have something else. I have my family, and my work and nothing else.

SIMONINI: Do you struggle at all with the work?

LAIB: I think most people, always from the outside, they think I am the happiest person in the world– sitting in a meadow with nature– but I think, to be a good artist, there’s a lot of struggle, and a lot of dissatisfaction. But if I didn’t have that in my life, I would be now a doctor and have a doctor’s office in a small town in Southern Germany. Not this.

SIMONINI: A lot of connections are made between your practice as a doctor and your work. Do you think you apply the kind of thinking you learned in school to your work?

LAIB: I think I never changed my profession. I feel I did with my art what I wanted to do as a doctor. That is for me, very important. And somehow people from the outside, think that it is totally separate, but for me it is not. And I could not have done this work without studying medicine. And without having also this challenge. The milkstone was really the direct answer to my medical studies. There was so much tension built up, over these years, and I could finally say everything I wanted to say, in a very, very simple artwork. The doctor today is somehow responsible for your physical body, he makes your lab tests and this and that, but beyond this, he has no idea how to handle it, or how to do it. Then he says I am not responsible for this.

SIMONINI: You often use the word ‘beautiful’ to describe your work. Beauty is very important to you.

LAIB: Artists hate that, especially German artists. If you wanted to be really hated in Germany, then you would say, ‘my work is beautiful.’ That’s really it for you.

SIMONINI: But you say it freely. Why are you so interested in beauty?

LAIB: Because I believe, in this world, German artists they believe in ugliness, and to be ugly and to be nasty, but I believe that this we all have. So, for this you don’t need an artist. It’s all there. So for what? So I think beauty can be something extremely important for our lives. And it’s not true that this is naïve, or not possible in this world. Of course, people will always say this world is ugly and so nasty and so impossible, you can’t make an artwork that is beautiful. It is totally out of place. But that’s not true. This is what is the most needed: inner beauty and outer beauty, which is an incredible challenge for us.

SIMONINI: Because you talk about this whole picture, are you interested in your work as affecting larger groups of people, in some way, as a social change? Is this interesting to you?

LAIB: Yes. I find such a pollen piece here, in the main space of MoMA, is a real statement, no only by me, by the artist, but also by the museum, of something which is very, very challenging. It seems so simple, and also formal, it’s just a yellow square, there. But if you really think what it is, and what is behind it, then it’s a real challenge to everything in the world. So it’s a real social challenge, on many levels.

SIMONINI: Have you seen work that has been a sort of catalyst for the change you are interested in?

LAIB: People find it very naïve when you say that, but I find that art always the culture, and culture was always much more important than politics. Finally, culture changed humanity, to another step, to another step, to something else. I mean, that was in history, it was always like that. There were these wars, and the king or the imperial did this or that, but I think art and culture had much more impact on the change of humanity.

published at sunrise

www.rosssimonini.com

www.instagram.com/rosssimonini