The work of Olga Balema is a satisfying defiance. She maintains a fluid approach to every aspect of her art: titles, forms, expectations and materials, which are occasionally actual fluids. Most often you can find her work resting on the ground, slumped or flat, and settling into the architecture.

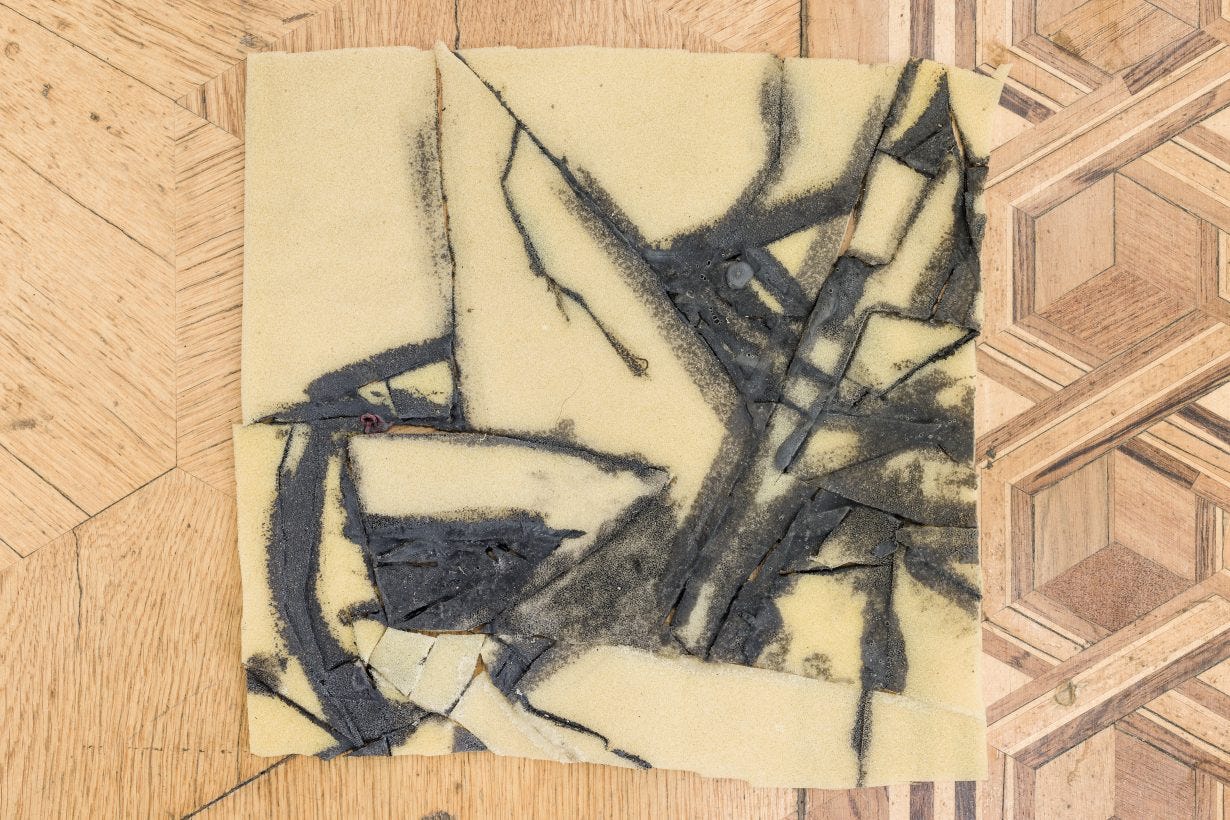

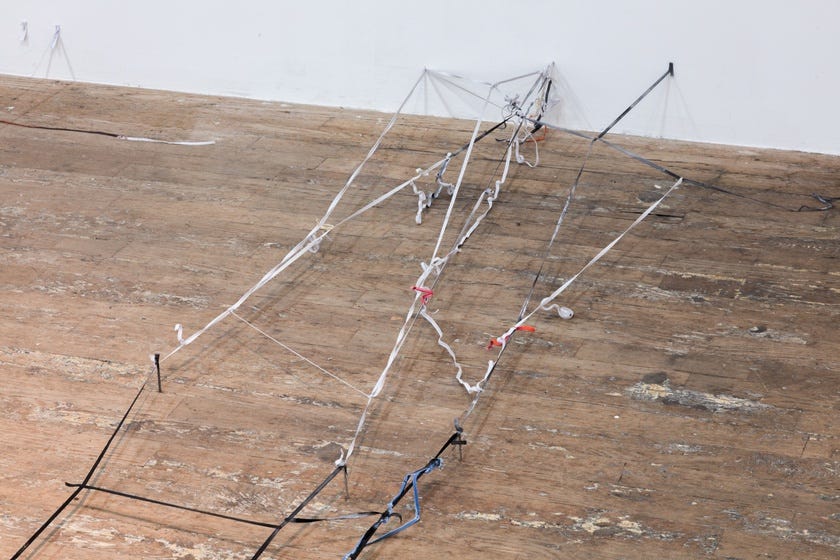

Her recent show Formulas, at Croy Nielsen in Vienna, is a collection of tilelike works, placed on the floor, where they appear to have been broken, then reassembled into elegantly inelegant collage. Her work brain damage (2019) is an installation of sundry spindly threads, stretched at ankle level: a patternless and beguiling web. Another work, Motherfucker (2016), exhibited at the Baltic Triennial in 2018, features sagging breasts affixed to crudely painted ripped maps.

For me, Balema’s works have always been characterised by mystery, especially her ongoing series of clear acrylic sculptures. Almost entirely transparent, they rest quietly between the wall and floor, without any interest in announcing their form. Looked at from a certain angle, in a certain light, they would not appear to exist at all.

This translucence is often accented by Balema’s modest installations and bare context. Many of her works are untitled, and in the past she has not been particularly vocal about her work, doing no interviews and making few written statements. But in line with her resistance to consistency, other work carries elaborate titles (eg, Manifestations of our own wickedness and future idiocy, 2017), and at times in the interview below she even responded loquaciously.

Initially when I reached out to Balema about an interview, she turned me down. But eventually we began to speak: first over the phone, then in a series of email exchanges. During this time, she was busy, intermittently sick and installing multiple shows around the world. Our exchange occurred over three seasons.

RS Where were you before the US?

OB I was born in Lviv, Ukraine, and we moved to Karlsruhe, Germany, in 1991. We stayed there for a year and moved back to Lviv, lived there for two years and then moved to Leipzig in Germany. After that we spent some time again in Lviv before moving to Ames, Iowa, in the US.

RS How did all these places affect you differently?

OB I had the idea to reinvent myself each time I moved, but I always stayed the same, except for the usual changes one encounters when growing up. It wasn’t always easy to adjust to constant change. Some places were more hostile than others. When I lived in Leipzig I was the most unhappy, but I also developed my interest in being creative then. I had a lot of time to myself and I would try to learn how to play guitar and record myself singing. I also spent a lot of time at music stores, listening to CDs at listening stations. There was a store called Mrs. Hippy that my friends’ older friends shopped at. It smelled very strongly of patchouli and a lot of goths shopped there. I wasn’t really allowed to buy stuff there, but I loved to go and look. There were a lot of different subcultures around like goths, punks, ravers, also neo-Nazis. Some of my schoolmates were already going to the Love Parade in Berlin at the age of thirteen. When I moved to Iowa at fourteen the scene was very different. The kids were much more wholesome in general, less angsty and edgy, more into sports and watching movies.

My most formative years were spent in Ukraine. It’s where I first thought, spoke, heard and saw, learned how to exist and relate to people, I’m not sure how to encompass that experience, because it’s the most distant and also most present. The tragedy of the war has made this distance/presence most palpable. I am safe from physical violence, but to know what a place looks, feels, smells, sounds like and now it is being blown up sent me into a different corner of reality, one I was unable to imagine before. And even with that understanding I can’t begin to approximate the reality and distress my family and the Ukrainian people are experiencing in face of the brutality and violence of the war.

RS Do you consider your history and identity to be a significant part of your work?

OB I think it shapes the why and the how, but maybe not what I make. By that I mean my history and identity are not the subject matter of my work. My work concerns itself more with formal explorations, materials that I encounter in my present, art-historical concerns, feelings etc. But I think how things end up coming out or what I am interested in has to with my history and identity. I would not believe myself if I said my work has nothing to do with my history. There is no escaping yourself. It comes through.

Read it in full here. And, if you like, listen to a newly released track I made back in 2007 with Lotte Kestner: