A Dialogue with Matt Mullican

“You’re in your body. You’re in your brain. You’re awake. And you’re watching yourself do these weird things. You’re just going along for the ride.”

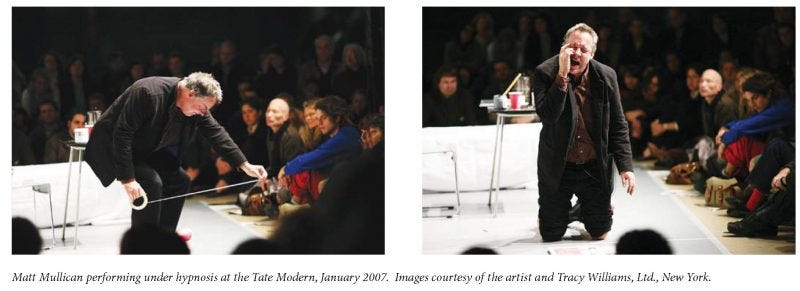

Before public performances, Matt Mullican is relaxed by a hypnotist, placed into a deep trance, and asked, “What would you like to do?” When he steps onto the stage—“a white void,” as he describes it—he is no longer Matt Mullican, he is “that person,” a dissociated abstraction of the self. Performances are often similar to one another and usually include crying, drawing, cursing, shaking, vigorous rubbing, squirming on the floor, compulsive speaking, and lots of self-derision. The point, for Mullican, is to get far enough away from Matt Mullican that he begins to understand the phenomenon of himself.

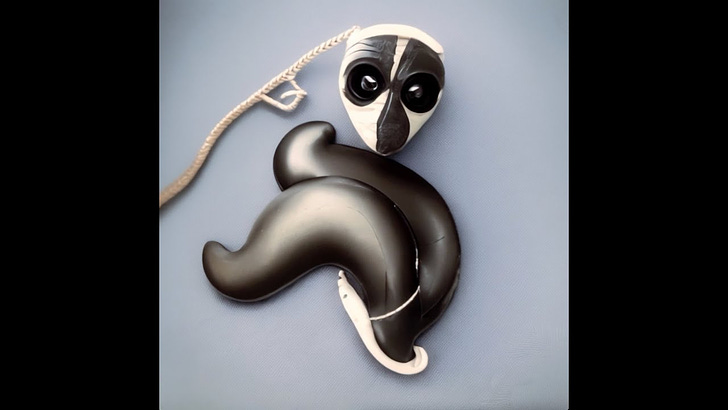

Though this sort of preoccupation is usually associated with psychologists and philosophers, Mullican is squarely an artist, disinterested in academic pursuits and analytical theory. In addition to his Under Hypnosis performances, he blows glass, paints signage, designs computer software, and draws stick figures—a wide scope of media and methods Mullican connects through his exploration into the “projection of identity.” His work gained attention in the ’70s, after he graduated from CalArts and began constructing his own cosmology and conducting performative experiments on a cadaver—yelling in its ear, sticking his hand in its mouth, etc. He is often associated with a group of artists called “the Pictures Generation,” and is, above all, a postmodernist with a persistent interest in the basic human response to symbols and meaning.

In 2011, after seeing Mullican lecture on a virtual urban environment of his own construction, I requested an interview through his New York gallery, Tracy Williams, Ltd. Several months later, when he made a trip from his home in Germany to Manhattan, we spoke in the Lower East Side studio he still keeps, among a roomful of his abstract cartography.

—Ross Simonini

I.THE PASSENGER

ROSS SIMONINI: When was the last time you were in a trance state?

MATT MULLICAN: [Closes eyes] Don’t mind if I have my eyes closed. It’s just easier. I do that if I have to concentrate.

RS: OK by me.

MM: I was in Newcastle. They had an MRI machine, and they read my brain in a waking state and in a trance state, to see how it changed. So I had a hypnotist, a very good one, and she put me into a real deep trance, and I was led into the MRI machine. It’s pretty druggy. A lot of times when you’re in a trance, there’s very few physical cues that you are in a trance. Your subconscious acts on it, but you don’t realize you’re acting on it. So as far as you’re concerned, you’re wide awake—you’re normal. But this time, I was aware of the trance. She touched me. This was the first time any hypnotist had touched me. She was brilliant. She picked up my right arm and then dropped it [demonstrating], just in the whole rhythm of what she was trying to do for me. So that was great. But when I was put into the MRI machine, I was saying, “Fuck you fuck you fuck you fuck you fuck you”—that was what my brain was doing. That was the art. It was just because that was the person I was in. And so that was the last time I was in a trance.

RS: You were aware the whole time?

MM: The whole time, you’re aware of it. But I believe your consciousness is not—you’re aware of it and still your unconsciousness is higher, has its own agenda, and it will do what it does, and you’re unaware of that. I talked to a doctor and I said I was doing this work with hypnosis and—this was at a party—and she said, “Oh, were you a passenger?” And that is really a good way of seeing it. It’s like you are a passenger. You’re in your body. You’re in your brain. You’re awake. And you’re watching yourself do these weird things. You’re just going along for the ride. And I remember the first time I gave a performance—this was at the Kitchen in ’78—I was a five-year-old character. So I was a child. But in my brain, I was thirty—and I was talking to myself. “This is weird.” “Look at this.” “Look what I’m doing.” I was chattering in my head.

RS: There’s a duality.

MM: And yet my body was acting. It was like, “God, look at your feet! They don’t look like your feet. Your body’s really weird. Look, why did you do that?” All this stuff was happening. You’re kind of two people at once, and there’s a back-and-forth. But I think we are different people in different places. We’re really contextually driven, I think. Like you’re different with your mother than you are with your sergeant, if you’re in the army, for instance.

RS: You’re switching social roles.

MM: I’m highly suspicious of the whole thing, and it doesn’t bother me when people say, “Ah, he’s not in a trance.” Being a “fake” has been a subject in some of the pieces I’ve done.

RS: Could you tell me about one of them?

MM: It was like having the angel on one shoulder and the demon on the other. It was almost a mother figure, saying how great you are, and how wonderful, and then the daddy figure was saying, “You’re a shit, and you’re an asshole, and you’re a fuck, and what are you doing, what are you trying to do up there, you’re an asshole up there, you’re a fake, you’re not real.” So what I was doing was, rather than being hurt by the audience, I was buffering that relationship by projecting my idea about what they were thinking about me. And I was going to beat them to the punch.

RS: Right.

MM: So if they thought I was a shit, I was going to say I was a shit before they could. So then they couldn’t hurt me. And that really got heavy. That was a tough one, because it’s so funny. There’s a lot of funny things that occur, but it’s brutal. The brain is not “on” or “off.” It’s like a million parallel universes. And they’re all together, and your ego and what you consider to be “you” jumps around in there, and sometimes you’re aware of why you’re jumping, but most times you’re not. You know, why do you do certain things? I mean, it’s just like “Why are my hands together like this, and what’s the history of that action?” I’m trying to understand that subconscious language, that vocabulary.

RS: What’s the performance experience like for you?

MM: When I go out onstage, it’s bright white, and it’s empty. It’s total emptiness. There’s nothing there. It’s like a void, a white void. And that’s how I feel. And when I go onstage, I basically always will go around the room, like a caged animal. You just go around the cage, and I respond to it and it’s just kind of physically getting acquainted. I’m rubbing my cheek against the wall, and my hands and my arms—it’s a funny sensation. And then it just starts to go from there.

II. IT CANNOT NOT HAPPEN

RS: How would you describe the way you act onstage?

MM: These different behaviors that come up—the autistic behavior, the schizophrenic behavior, the compulsive behaviors that occur, the sense of Parkinson’s—the shaking that I go through—that, this, this rhythm that occurs, and the Tourette’s thing—this kind of swearing, this continuously swearing, this “Fuck you, shitface” that goes on, trying to be the nastiest, nastiest person—where is that all coming from? And when I go into the trance, I’m going really deep down, where the filters are off and I’m just floating around in my head, and I’m going into these—letting myself go into this place I generally try to protect myself from. We don’t want to act that way.

RS: You don’t like “that person.”

MM: And there’s a backlash to that. So now my kids are so highly aware of my character, they see me acting like this at home and they’ll point it out to me—“Oh you’re acting like that person.” And I will see myself doing that, and that’s something I was never like before.

RS: You’re saying the performances and hypnotism are bringing this out in you. You’re becoming that person.

MM: But I’m fine, I’m a waking person, I’m a normal person now. I’m not—if I give a lecture, you’ll see that I give it with my eyes closed or, you know, I’m in another place. But I’m interested in this autism. Not that I am autistic—but I’m acting like I’m autistic. My motivations seem to be very similar to an autistic person’s. Total insulation. Singing and memorizing and counting and alphabetizing.

RS: You’ll put down the masking tape, too. I’ll notice that you tape off an area during performances.

MM: Yeah, and I was really happy with putting the transistor radio to my head and putting it to static. And it could just be a relationship to the audience, that I cannot handle the fact that I’m in this dual reality that I’m in, and in a relationship to the audience, that I put blinders on to the audience—that I cannot see them. I asked the person in Geneva, “So, what did the audience think?” and he just said, “Autism.” They all thought I was autistic.

III. TAKING OUT THE GAME

RS: What’s the intention behind the hypnosis?

MM: That’s a big question. I really started around 1971, ’72, and this is right on the heels of conceptual art, minimal art, really objectively based art. And I was just looking for room to breathe, because everything was so closing down in the art world. You could only do certain things. The etiquette was so powerful, of what you could do and what you couldn’t do. As a younger artist, I wanted to go against the etiquette. So I wanted to not deal with the paper, nor the paint, nor the photograph, but I wanted to deal with the subject matter. So I did these drawings of a stick figure, and I named him Glen, and he was in a studio, a fictional studio, and did all this stuff in that studio. He pinched his arm, and he closed his eyes, and, you know, I did five hundred drawings of him doing a lot of different things. But really what I was trying to do was to prove that he was alive—that the stick figure lives. And it was about going into the picture. So rather than saying the picture is a physical object, I was saying it’s a psychological object. It’s not so much about it being there; it’s about what I see when I look at it, and how my body changes when I look at it. For instance, I did all these drawings of pornography, where I just traced from porno magazines, intercourse and blow jobs and whatever else, and if I showed it to a teenager, they’d get a hard-on. So it was about—the picture becomes powerful, and you’re entering it. You become part of it through empathy. And in a sense that’s what I was interested in: when the stick figure pinches his arm, where is the pain? Where does that pain exist? Do I feel when he pinches his arm? And that’s the same pain that you feel when you see a photograph of someone getting a hypodermic in their arm, or when someone is hit hard in the movies, or if you go to a boxing arena and see people beat each other up. There’s this visceral kind of relationship that you have to it all.

RS: Is that not empathy?

MM: That is empathy, and I was interested in it. And when you get down to it, this is kind of like when my son plays video games—he is so inside the game, his body is moving. He has no awareness. I could see his body moving all over the place as he was in the game. And hypnosis is like just taking out the game. And there he is. He’s moving around. Hypnosis is, in a sense, taking the media away and seeing what’s left over. That is the empathy without the structure.

RS: How would you say this is related to acting?

MM: When I got to theater, that was like the world frame, but then I thought, Well, what if the actor believes they are who they are portraying? And this seemed like supertheater to me. The first piece I did was at the Kitchen, and I hired three actors to play Details from an Imaginary Life (from Birth to Death), which is a piece that I wrote in ’73, and it was like—there must be two hundred and fifty statements, and they acted out about thirty of them in front of an audience.

RS: Were the people hypnotized?

MM: Oh yeah. I hired hypnotists, and then I became this so-called “control freak” because I was controlling them, and it felt like, kind of 1984, Gladiator, some psychodrama thing that people were witnessing. It just seemed very odd. And then, at that point, after I was accused of all these bad things, of manipulating people to do my stuff, I said I would only do it myself, and I would not have actors doing it. So the next performance I did, I had myself do it.

IV. DRINK COCA-COLA

RS: I’ve heard you use the term projection of identity, and I wonder what that means.

MM: It’s not your full identity that you’re projecting—it’s just an aspect of your own identity. That’s how advertising works, you know?

RS: Right.

MM: I remember sitting with a friend of mine—this was in the ’80s—and we were at the Spring Street Coffee Shop, and we were at the counter, and he ordered a Coke, and he said to me, “God, I haven’t ordered a Coke in years. Why do you think I ordered a Coke? How weird is that?” And then I pointed in front of him. There was a Coke machine. And on the Coke machine it said, drink coca-cola. And I just pointed to it, and then he hit his head, like, “Oh, my god.” Because we assume that we are in control, that the objective world will always win out. I always talk about “that person.” That character that I become. It’s not a single person, but it’s that person. It’s not a he. It’s not a she. It’s not a young. It’s not an old. It’s that person. It’s a person on the street that you do not know.

RS: This is who you are when you’re hypnotized?

MM: When I go through a magazine, for instance, I cannot help but identify with that person. I don’t mean to. And it’s not my whole psyche that’s doing it; it could just be some minor little fly, but it’s still happening, and it happens whenever. You can’t help it. You just do it. It’s like blood pressure. We do it continuously. Whenever we see someone, whenever we meet them, there’s a huge kind of agenda of how we contextualize who we’re meeting, and we empathize with them, and we figure out who they are and what they’re doing, and it’s a kind of a self-protection thing that occurs.

RS: How does your work connect to fiction, to the novel? Is Glen a fictional character? Is That Person? Or is it something else?

MM: It’s as if you took any character and you basically took the story away from them, but you kept the empathy to that character. You kept that part of them, and then you just displayed them. That’s pretty much what I do.

RS: How is Glen different from, say, Raskolnikov? I mean, if you took away all the words from Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov is no more.

MM: Yeah. He’s gone.

RS: But Glen’s still there.

MM: That projection, that magic thing that occurs when you physically are so engaged that it affects your body, when it affects your mood. And Glen is, in a sense, that—that, ah, what’s the word?

RS: Avatar?

MM: Yeah, avatar. You as that character. That is who Glen is.

V. EMPATHETIC REALITY

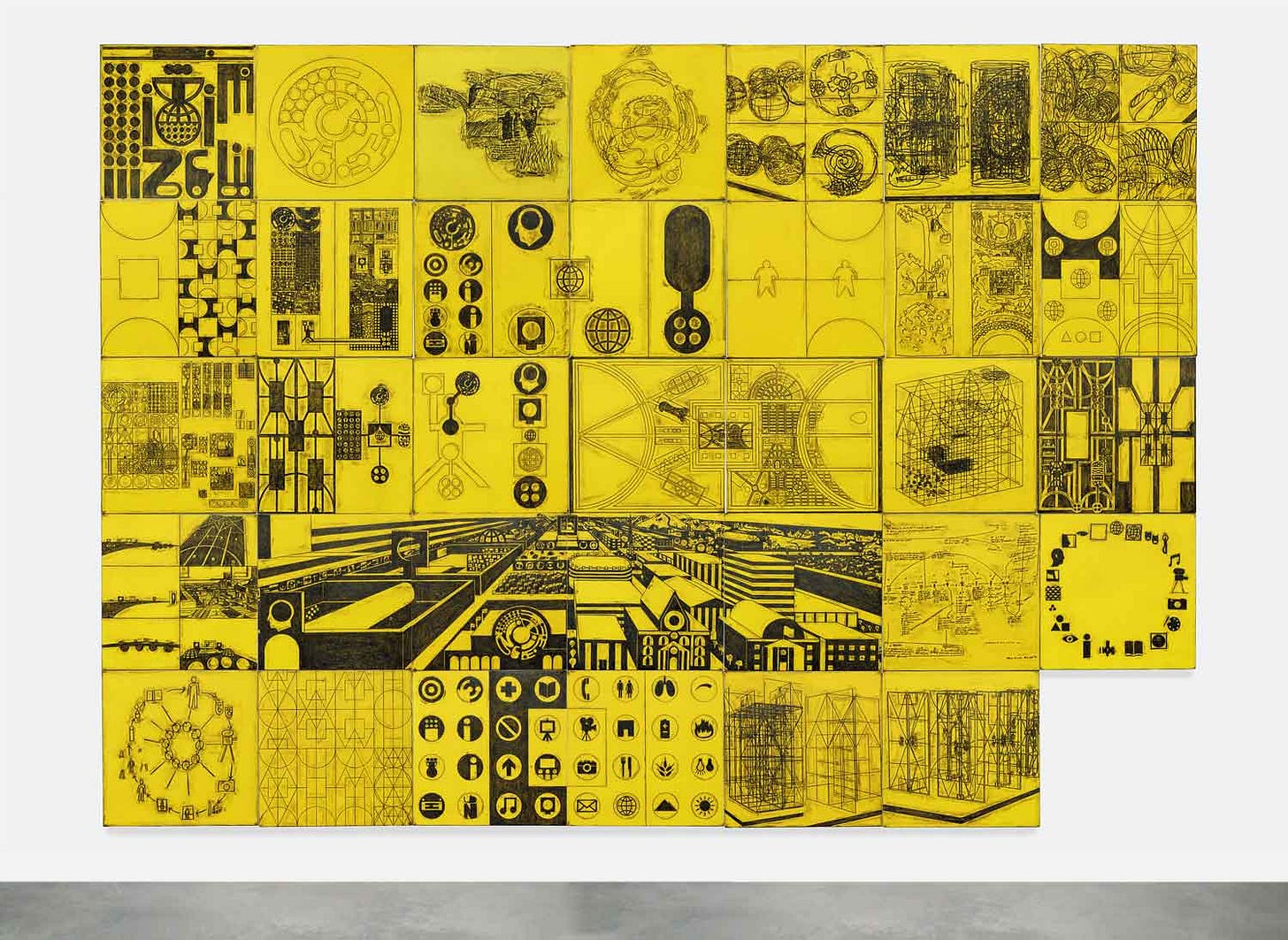

RS: A lot of your work is about symbols—your flags and drawings—but does anyone understand what they mean?

MM: I use these symbols that are so abstract that there’s no way people are gonna understand them. Some signs everyone understands, we think. I did a flag in India and it was the symbol of the world. The World Bank has the same sign. But I’ve used it in my work for thirty years, and so what happens is that, uh, this tailor does it for me, and he presents it to me, but it’s sideways. It’s not the world sign. He didn’t see it. Brilliant tailor, but he did it wrong. And I didn’t tell him what the top and the bottom were, because I assumed he saw what I saw. But he didn’t. He didn’t see it as the world at all, he just saw it as a nice, decorative thing.

RS: A pattern.

MM: Just a pattern. And that was kind of interesting for me. So, when you get into my cosmology, which is so subjective, who’s to say a target is the sign for heaven? Or that the man turning into the target is the sign of God? No one’s gonna know that. If I have that on the outside of a building, people are gonna see a target. It’s very strong-looking. I have a banner that’s in Antwerp, and it’s seen by masses of people on the highway. Not one of them knows what it means. I mean, they don’t have to know, necessarily.

RS: So then what is its function for you?

MM: Well, it functions for the people that know it, for starters, and then it functions as a graphic image, it becomes abstract, so it becomes a visualphysical phenomenon that’s up there. So it’ll act as that, and then if you want to, you can find out what it means, if you want to go into it, you have that option open to you. But it’s not only gonna work if you know what it means. When I go to the Egyptian wing of the Met, I have no idea what most of the stuff is. Most people don’t.

RS: The hieroglyphs.

MM: Yeah. Or a map of Paris [points to a map on the wall]. I mean, most Westerners would understand that’s Paris. But I’m sure that if you showed that to a lot of people, that they wouldn’t even know that that’s a city.

RS: So you’re talking about abstraction, maybe? The symbol, the symbol of a place or space.

MM: If I make a drawing of a plank that is five hundred yards away in a virtual field, I could feel this space. I used to call it an imaginary universe, or a fictional reality, and then eventually, when I started to work with computers, they called it “virtual reality.” Now it becomes this empathy that I’m dealing with. That’s the word now. Empathy is a catchword right now. It really is. I mean, the brain and empathy are so hot. You go to the bookstore and you see all these books on it. It’ll pass.

VI. THE ROLE OF THE ARTIST, WITH BIG, GIANT QUOTES AROUND IT

RS: Is your personal cosmology a belief system?

MM: No, it’s a model. It’s not a belief, but that model started with beliefs, when I was a child. When I was a child I believed that before I was born, I chose my parents, and that I was on a conveyor belt, and that they were there and I saw their names and I—and I went down a chute and went into my life.

RS: The Industrial Revolution cosmology.

MM: It’s a cartoon. It’s a Warner Bros. scene, where you see Bugs Bunny before he was born, on a conveyor belt— it’s like that. And then that fate controlled my life; he was watching a TV set.

RS: He?

MM: He is fate. Fate was pulling on a lever and saw me and controlled my life by pulling on the lever in a certain way. And that was fate’s control panel, and I believed that as a child.

RS: Death also seems to be a big part of your work.

MM: I did a performance with a cadaver in ’73, at Yale University, where what I did to the cadaver is what the stick figure did to himself. So I slapped the cadaver’s face, I pinched the cadaver’s arm, I yelled in the cadaver’s ear, I put my hand in his mouth, I dealt with the senses, I was going the opposite of how they were treating the cadaver, which is a body. So I was going into the head.

RS: It doesn’t sound like you’re interested in truth.

MM: The truth of the sign, yes, but not the truth of death or fate. I would never say what death or God is. How could I? If we both decide that pole [points to a pole] is God, and this is actually a sacred place, and then we start convincing our friends that that pole is God, and then it somehow grows and it becomes a whole social thing where we have meetings every Friday night about this pole…

RS: Sounds fun.

MM: …and then the cosmology exists as a social phenomenon. So until I convince someone that my cosmology actually is the truth, which I never would want to, then it’s not gonna be real, it’s gonna be a fiction. And it’s fine for that. I am a postmodernist. I’m not so concerned about the cosmology being real or not. I want the debate to occur.

RS: It’s about the cosmology itself, not about the truth behind it.

MM: It’s the difference between postmodern and modern. I think modernism has something to do with this idea of the goal, the end. That modern compass was so clear. I think everybody that was doing what they were doing in 1967— they knew that they were doing important things. This was consequential. They were making consequential art. Whereas now we can make a lot of money, we can have big galleries, but I don’t know if everyone’s so convinced about how important what they’re doing is. People say, “What’s the point of making the cosmology if you don’t believe in it?” I say, “I believe in believing.” So I have that one step away.

RS: That’s the postmodern step.

MM: Yeah, that’s the step.

RS: What are your feelings on classical philosophy?

MM: I graduated in the bottom tenth of my class. My education was not fabulous. Whenever I give a lecture, at the end of my lecture there’s inevitably a couple of people wanting to know about this philosopher and that philosopher and how much did they influence my work—Kant or Foucault or Derrida.

RS: Mind-body stuff.

MM: So I get attacked by a student saying, “You should really know that backward if you’re doing the work you’re doing.” “Ah,” I say. “But I don’t.” I’ve come across their ideas in the culture. Those concepts are not invented. If there’s actually some truth in what they are saying, something that has to do with the nature of reality, then someone else could understand this without knowing about those philosophers. If I am working in philosophy, it’s a really primitive philosophy. When I go into a trance state, and I’m doing what I do in front of an audience, and I’m going into it, I’m objectifying my own psyche. Like a found object. I’m distancing myself from myself. I’m trying to understand what art is. I’m trying to understand picture-making. Why do we do it and how do we engage in it and what’s the vocabulary of it and what is the depth of it? What’s the surface like? I’m doing something that is so traditional. The role of the artist, with big, giant quotes around it. The artist as the channeler, as the person who has the hand on the ground who can tell you if it’s going to be a good spring or a bad spring.