An interview with Lonnie Holley

plus a podcast on riots and a song of failure

1.

A few editions of “I Fail” are still available at NINA. A second version coming soon.

2.

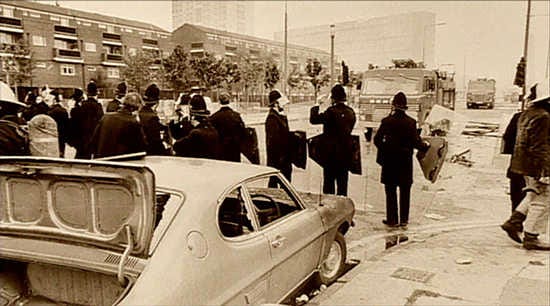

A new episode of Subject Object Verb is out now: on podcast on riots, uprisings, and pogroms with Natasha Ginwala. Listen here to mixtapes and sound collages by Arshia Haq (writer, filmmaker, DJ), Louis Henderson (artist, filmmaker), Josh Kun (author, music critic), and Atiyyah Khan (arts journalist, music writer, artist).

3.

As he tells it, Lonnie Holley began singing at birth, fathered his first child at 15, and discovered art at 29. He was raised in Birmingham, Alabama – “down by the river” – and his life story has the weight of legend. He’s the seventh of 27 children and now has 15 children of his own, by five different women.

For Holley, making art is his way to therapeutically address the deep traumas occasioned by an intense life. Whether or not his stories are entirely true, it’s clear that his early life was dense with struggle. He was incarcerated in a juvenile detention centre. He experienced a severe car accident that left him briefly brain-dead. He dug graves for a living.

As a visual artist, Holley mostly works with found materials, especially those coated with the patina of time. He’s drawn to tree branches, broken electronics, ragged fabric, old tools and plastic packaging – junk, as he calls it. “I take things and I put them together,” he says, “and they end up being what humans call art.”

In his Atlanta apartment-studio, these assemblages dangle from an environment of thread and wire, and in his former home in Alabama – demolished by the city for new development – they filled the front yard like a visionary environment. On their own, the sculptures are talismanic, but in his studio installations they evoke a neural network of compulsive creativity.

A few years into his object making, Holley was brought under the aegis of art historian Bill Arnett’s Souls Grown Deep foundation, which documents and preserves the tradition of African-American Southern artists, including masters like Thornton Dial and the Gee’s Bend quilters. Holley is self-taught (his education stopped at seventh grade) and his work certainly expresses the raw aesthetic of outsider art; but his objects also sit nicely alongside the crude artifacts of Jimmy Durham and the junky elegance of Robert Rauschenberg and Ed Kienholz.

For most of his life, Holley’s work was known only regionally: in 2004, the Birmingham Museum of Art held a 25-year survey of his work, entitled Do We Think Too Much? I Don't Think We Can Ever Stop. Five years ago, Holley began working with James Fuentes Gallery in New York, and has since held multiple solo shows and appeared in group shows alongside established contemporary artists. Nevertheless, he was featured in the definitive ‘outsider’ exhibition, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

Meanwhile, Holley has begun releasing his music: three increasingly impressive albums. He’s toured and collaborated with a variety of younger musicians, including Bill Callahan and members of Deerhunter and Animal Collective. His music is often improvised, and his songs are usually ephemeral creations of the moment, never quite repeated. His newest record, MITH (2018), pushes his psychedelic soul poems into aggressive, political directions, and colours his sound with sharp, contemporary production.

Holley continues to work and tour at a constant clip. In person, he has the joyful energy of a child, hungry for experience, fascinated by the world around him. I spent the day with Holley in New York and we spoke for several hours, but the encounter was less like a back-and-forth interview and more like a sermon, with occasional interruptions by me. His preaching was musical. He dropped quotes from the Bible and his own lyrics, and made near-constant observations on the minutiae around him.

We initially met in my studio for the talk, and we discussed both our work at length. Then we strolled through Chelsea with my wife and Matt Arnett, who is Bill’s son and works with Holley through Souls Grown Deep. Holley was uninterested in the galleries and mostly stayed outside, wandering the streets, head down, hunting for urban treasure. By the end of the day, he’d fashioned a hanging charm from zip ties and a railroad spike, which he gave to me as a gift for our talk.

The following month, I received a text from Holley with a picture of a new sculpture he had made for me. He’d made and left it on the streets of Manhattan, and gave the address where it was located. A few hours later I went to seek it out, but by the time I arrived uptown, the busy flow of urban life had already washed the work away.

Ross Simonini: I’ve noticed some welding in your work recently. This seems a radically different process than the homemade objects you’ve made in the past.

Lonnie Holley: I didn't actually weld the pieces. I was at a hundred-year-old junkyard, so the policies were that the artist that comes in can't use the torchers and the welders on the site. But I'm kind of independent whe

n it comes down to doing things. I prefer to do it myself. At times that help is really necessary, though. It's like you and me today, talking, but we're not just sitting here talking. We got this machine that is recording, therefore we have our helper that is helping to deliver the conversation out to others. The process of that is so much more: you got to look at the kilowatt, the power that these machines need, you got to look at the making of the machine itself. We as humans, we have a tendency to do things, but we’re not seeing the overall outcome of it. That's our greatest mistake.

In the Bible, it say, study, to show they self approved with action as an artist and a musician, I'm still learning. When you invite me to come talk, I'm talking about the experience that I've experienced, and that may go all the way back to the smallest little run of solder that melts these lines together, that allows the technical ability of this technical machine to work. So in a sense, I don't want nobody to try to brain it like I do. In a sense, we need to learn what our brains can do, but I'm not here to force nobody to appreciate the whole level, the whole concept, of everything. I'm on the other side of the pulpit. I'm not behind it. I'm not looking to make myself presentable to an audience every Sunday. My kind of presentation is for sixty-sixty-twenty-four-seven. 60 seconds, 60 minutes, 24 hours. You see what I'm saying?

The Bible also says, watch, as well as pray. The term of that, to me, was to look at other people's habits as well as communicate. Praying is like pleading, asking for something, asking for attention from someone. If we put it in a spiritual realm, it's a god. We put in in the realm of the holy one, the high thinker, the intelligent one. But also: mother, father, grandmother, grandfather, uncle, auntie. Relatives with the ability to teach me something. Praising means to put you in a memorial position: I'm thankful for you, therefore I dedicate the movements of myself, my capabilities, all I do. I want to make everybody that has served me proud of what I do. I want to show my capabilities, I want to show my performance, but I want to be the best at what I do. I want to show them I worked all these years. I worked since 1979 in art. I want to be one of America's greatest artists. I want to be always on the job, always!

RS: What do you mean by "always on the job?"

LH: Always on the job is me walking down the street and seeing all the trash on the street and wondering where will it go? Or seeing all the leaves that's falling off the trees that blew along without being raked up. Or going underground, and looking up, and down, and looking around at the steel beams, and thinking, Do peoples really understand the deterioration of a piece of iron when somebody says it's rusting to pieces? It's rusting to pieces because of the dampness that's down in the ground anyway. You got granulated grains scratching against whatever surface keeps the tunnel from collapsing. How many grains of sand could go through a needle, but they say that a rich man cannot enter into heaven because he could not fit through the eye of a needle? Does that mean that the grain of sand could get into heaven before we as humans can? Yes it can. Yes it can! A grain of sand could be picked up with the wind and blown along with a storm. If the heavens is no higher than that much space off the Earth, and all that atmosphere between Earth and all the other planets, if Mother Universe is considered to be the container of the heavens, then who must we praise, if it's not Mother Universe, you see?

I say, thumbs up for Mother Universe and her gumboise manner! I love gumbo. I know what it takes to make a pot of gumbo. I know that you have to stay right there, and you have to continue to stir it as you add ingredients, and it won't stick. It won't burn. And as you add those ingredients, you can't go churning it like milk. That's not good, 'cause you mash everything. You want to stir it properly. Every bit of every thing in the action of the universe is in the process of stirlation. Everything has got a stirring order. If we just learn to appreciate it, and understand that our brain contain all of this information if we desire to have it. If we just sit and think, we wouldn't try to push ourselves beyond the current of reality. Sometime we overdo ourselves. We kill ourselves too quick. We put too much force on something that has a force container of its own. All these energy drinks and things like that people's drinking, they don't need them. They's taking themselves away from the natural. They can't love themselves in the natural. When you've energised yourself, your brain has gone too fast to even recognise your body. You're constantly putting on make-up. You're tearing at your body, trying to make it the finest, when it was integral of the finest just by the process of natural growth. I wish I could have kept it all. I wish I could've.

RS: You speak like an improviser.

LH: Do you not see that life is in the act of that you just said? Life don't go around announcing the layout of the manner that it is. It creates the manner that it is. Therefore, we be within it. That leaves what? That leaves our brains to make the decisions of how to deal with it. It's up to us.

RS: Do you feel like the music and the lyrics function the same way to you as talking to me right now?

LH: If you had asked me to come in here and sing it, I would sing it the same way.

RS: What did you listen to growing up?

LH: I was raised with the big band. I was raised up with [American bandleader] Lawrence Welk. I was raised up hearing instrumental music in the background of movies. I was raised up going through the state fairgrounds and hearing all the different kinds of musics and sounds and then coming to the point of seeing and centralising these different types of sound. So, we need it. We all need to take a course on hearing. I get so intense in my hearing that I can hear the crawling things. I can hear things walking and stepping and breaking leaves and sticks as they step on the ground.

RS: Were you raised with religion?

LH: My grandmother didn't force me to stay in church with her, but she took me there. Therefore she took me somewhere to learn of a manner. She also took me to the graveyard when she dug graves. She took me there and I watched her manner. I also watched her at her house, almost at the ending of her life. I remember one cold day I had when I was at my mawmaw's house, my grandmother, my daddy's mother, and she was in her room, and she was laying there looking out the window. Then, the next morning, she had got up. She had this one little fireplace in her room. One little kind of gas heater. I watched her. She got it. She make a rack with some bricks right in front of the little gas heater. The flame was coming up just like that. So she made a rack, she set the skillet up there, and then she fixed me breakfast right in that skillet. I never forgot that. Something had happened to her house and she had to do without the kitchen appliances and everything. So she took me out in the backyard, and she took some bricks, she took a sheet of tin, she took it in the house and she washed it real good, smooth. She brought it back out and she took the grease and she greased the tin. She did the pancakes. She did the eggs. She did the meat.

Those were considered to be primitive acts of survival, but don't we need them now, when the people's houses and things get burned now? I'm so afraid of what fires have done and the aftermath of fires, the animals, and the creatures, all those things trying to run away from fire. And animals that was underneath found their burrows and got up underneath the rock and survived still had to come out and try to move around on top of this heated situation. Can you imagine what that was like? Little bird's feet and toes just cooked off! They running around on the nub of their legs just trying to get to freedom. These are things that we cannot see and we don't want to see because we call them horrible. We don't want to deal with horror, but we pay for horror films. We want the fantasy of the horror, but when it comes down to natural horror, we don't want to face it. My whole thing is, why not, if we're to change it?

On the way down here, I was hearing this man, right there before we stopped at the station to get off to come to your house. It was a man sitting playing his keyboard. It was Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come. It's almost like his spirit was connected, and as he was coming to the end of it, he smiled. A change is going to come. It's not here all the way, because it never stops changing. I know that I'll probably be dead and gone when the change comes. You can say it now and it'll take 30 years before it'll be activated into the system. You see what I'm talking about? I try to tell people, beware, and be wise, and in the process we will attain wisdom. We will become the wisdom keeper and pass on the wisdom.

RS: Do you feel like that's role of art? The communication of wisdom?

LH: If you got a place that is prone to be dangerous areas, I believe all you gotta do is have a few concerts in that place. And have different concerts, don't try to just have one, because everyone is different, and their hearing is different, so they don't just need one type of music brought to them. All kinds of communication.

RS: Is this how you usually communicate with people, the way you’re talking to me now?

LH: No. I can't just see out in my hood and talk to everybody like I'm talking to you. Everybody can’t – is not even worthy to hear what I'm saying because they're not going to do anything with it, so why waste my breath and time saying things?

RS: What kind of energy does it take for you to show your work in public? In the artworld?

LH: A lot of these peoples, they go to museums, and they get involved with shows and things, but they actually don't get it. They don't give themselves enough time to get it. They really don't put enough time in investigating the piece of art that is brought before them, especially if the piece of art is rare and different and for a specific cause. If you're not examining it, you won't get its message. And that's why they miss a lot, they miss artists such as you and me. They're misinterpreting our work. They'll put it in the realm of, "Oh, he's abstract. Oh, he's using that junk, that trash, that garbage. That stuff, that's rotted wood, that's rusted tin. I know about that stuff." Not really. You don't know about that stuff. And you don't know the term, “I was born down by the river.” I was born down in the country! I was put out in the midst of life as it were in the fullness of itself. I was taken away from my momma at one and a half, I was sold into a whiskey house at four years old, and I had to grow there. I had to get out of the house at five years old because of the grown people's conversation and all this other kind of stuff. I went down the ditch with my little fork and my little bucket, and dug for worms. It was an adventure ‘cause all of these little worms you be trying to catch are on the run. Every time you expose them they run. I put some humans in the action of a worm, because as soon as they're exposed they go running. They don't want people to know them like that. We're running from the atmosphere. We don't want to get sunburned. We don't go out and deal with the cold. We stay in. We turn up our furnace.