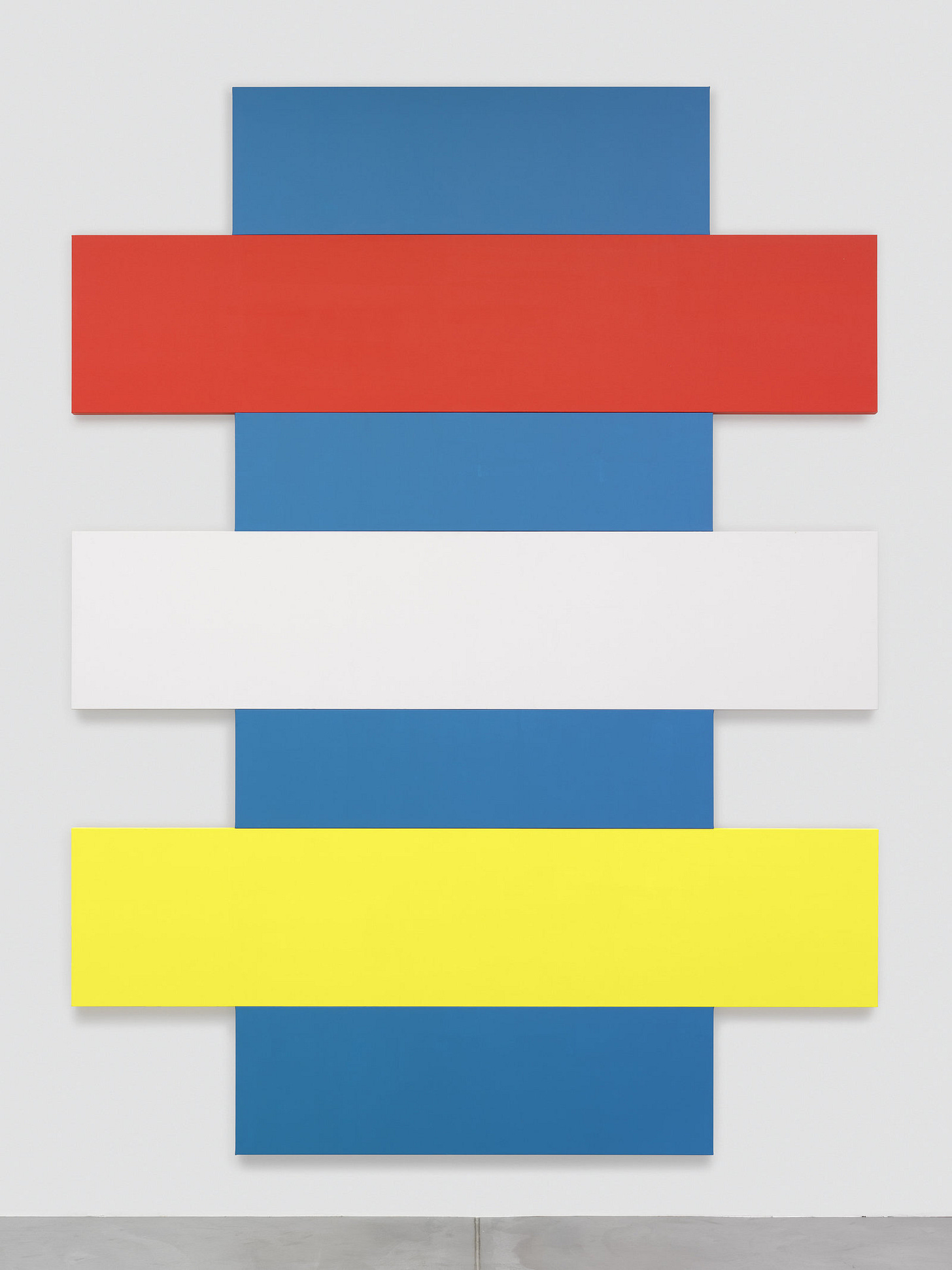

For years, every time Joe Bradley made a show of new paintings, they appeared to be the work of a new artist. When he showed his stacks of colorful, modular panels, they suggested affable robots and regal sailboats and the whole lineage of geometric, monochromatic painting.

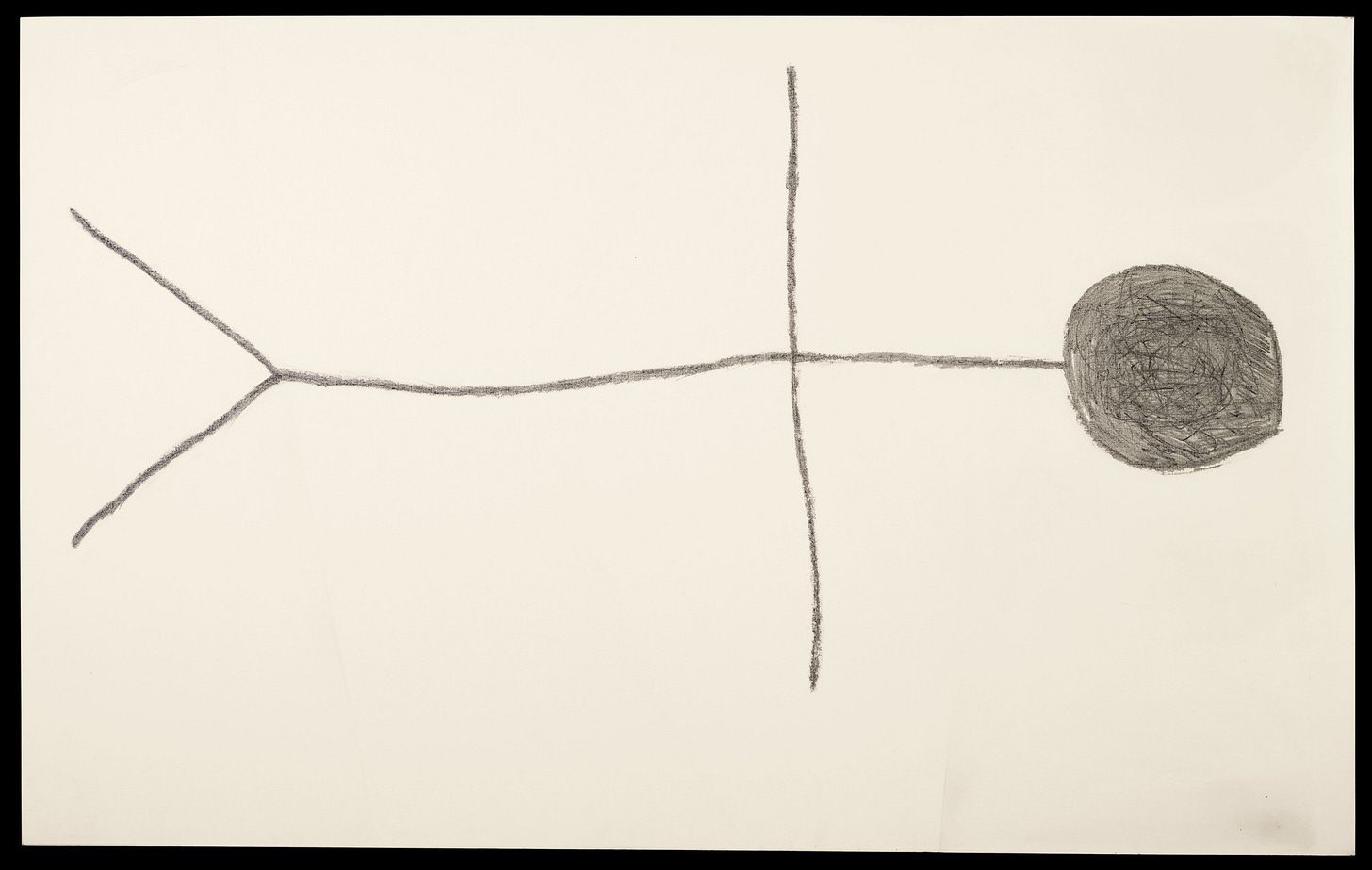

Later, he made a group of “schmagoo” paintings—big canvases with single, crude grease-pencil drawings of the most dumbeddown icons—a fish, a cross, a Superman logo, a stick figure— completed in what appeared to be a matter of seconds. Other shows have included screen prints, doodles on scrap paper, spartan collages, and blank tan canvases with painted frames.

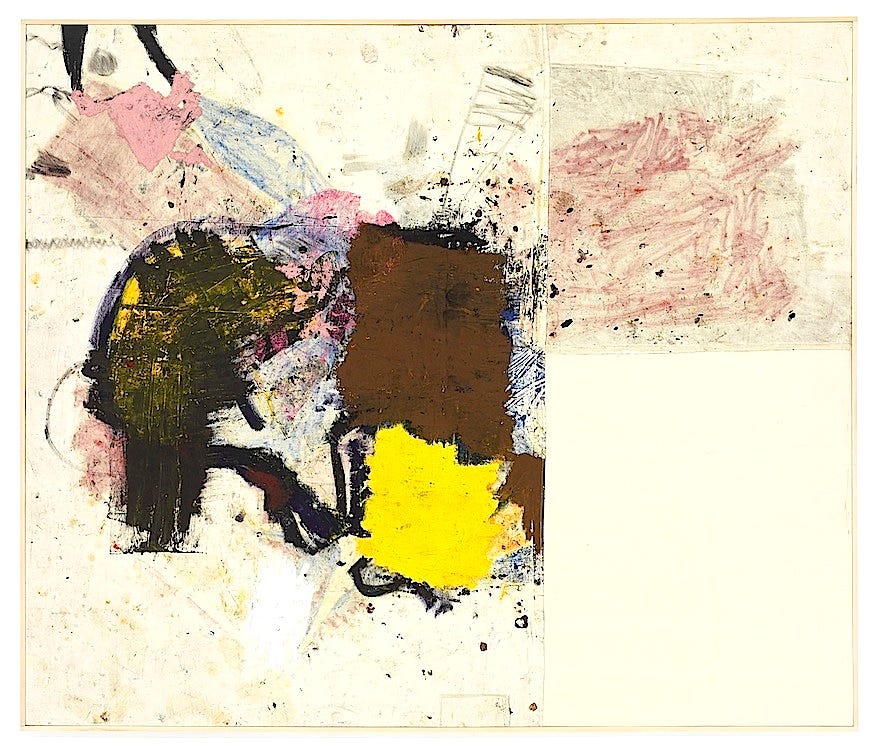

More recently, through hopscotch experimentation, Bradley has settled into a more consistent style of abstract-figurative painting. Using oil-paint sticks, he draws on raw canvas with the abandon of a feisty child searching for a subject. Intermittently, he’ll drop the half-finished pieces onto the floor and let them roll around until they accrete a patina of “shmutz,” as he calls it. Sometimes he’ll stitch together multiple in-progress canvases in an effort to further “glitch” whatever techniques mhe accidentally acquires. In this way, he’s become undeniably skilled at making the unskilled mark, and the results are transcendent: standing in front of his new work stirs up a visual epiphany of lowbrow wisdom.

For this interview, I visited Bradley twice: once at his old studio in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn, and later at his current, exponentially larger space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The new studio has allowed his paintings to expand in size, and the entire multiroom complex was covered— floors and walls—with drawings and paintings, near ready to be shipped off for a European show.

As we spoke, we flipped through his piles of art books and Bradley smoked more cigarettes than I could count. A few days later, I ran into him in my neighborhood, where his boy, Basil, was buzzing around the block, and we discovered that we live only a few feet from each other. The below transcription captures the beginning of the conversation that now continues, every so often, on the sidewalk in front of our homes.

I. On Grandma Moses

ROSS SIMONINI: So we have seventeen hours left on this recorder.

JOE BRADLEY: I don’t know if that’s going to be enough.

RS: You want to talk about paintings?

JB: Or…

RS: Or let’s talk about your love life.

JB: Well, seducing a woman is an art unto itself… [Laughs]

RS: The first works I ever saw by you were the monochromes.

What were you doing before those?

JB: It’s always been painting in one form or another. For a while it was intimate little abstract paintings, objectlike paintings. Sometimes it would just be a piece of fabric, stretched. The sort of “sleight-of-hand” painting that seems popular today. They looked a little like Blinky Palermo, although I was unaware of Palermo’s work at the time.

RS: And was that at RISD [the Rhode Island School of Design]?

JB: That was in New York. At RISD, I was making landscape paintings.

RS: Traditional landscape paintings?

JB: Kind of. I was looking at the worst of the genre, Thomas Kinkade and that kind of sentimental, nostalgic landscape painting you might come across in calendars or postcards, but I was also thinking about Marsden Hartley and [Albert Pinkham] Ryder and these guys. We see so many images of sunsets. It’s an image that has been so abused that it’s kind of lost all its meaning. But then it’s also a beautiful thing, and it has the potential to be very meaningful. So I was doing that, working on these things, for probably four or five years, and then I moved to New York and somehow the interest in that stuff just dried up for me. It didn’t feel right, living in my little hovel in Bushwick, trying to paint like Grandma Moses. I had been making these abstract paintings as a side dish, and those just ended up being more interesting to me.

RS: Abstract being the monochromes?

JB: They weren’t all monochromes. But the monochrome was appealing to me because it seemed so dull and sad. I had no interest in monochrome painting, and I didn’t really care why other people made them. I knew that it was supposed to be about painting, but I thought it might be interesting to approach making them on an emotional level.

RS: What do you mean, “an emotional level”?

JB: Just out of frustration. Out of being bored and frustrated and not feeling comfortable putting one color next to another.

RS: The ones I’ve seen always appear to have been stacked or arranged. Did you think of them as one big painting?

JB: The stacked monochrome paintings came after. Initially, they were conventional single-panel things. I had been thinking of them as having personality, or hoping they would have personality. I liked the idea of a painting having a sort of ambience, giving off a vibe. Like you could look at one out of the corner of your eye like you would a stranger in the room. And so making these kind of schematic figures was just kind of a really dumb way of handling that, an obvious way to amp it up.

RS: A really reductive figure.

JB: Yeah, and I thought it was just a funny idea and a good idea. It actually came to me in a dream. I woke up one morning and it was there. But the reaction to those things— I think they were read as a critique of minimalism. Kind of taking the air out of it, which was troublesome. It wasn’t really where I was coming from. My big idea at the time was that you… rather than emulate or respond to the work that I love, and attempt to expand on it, I would pick up on something that I felt no real connection to, and hoped that by working with this foreign stuff my sensibility would pop up in some interesting and unexpected way. I think it works, but it’s something that I’m shying away from now. It’s refreshing as hell. I actually look forward to coming to the studio now.

RS: Sounds like you were punishing yourself on purpose.

JB: I was.

RS: Were you raised with some sort of repressive religion?

JB: Well, I was raised Catholic.

II . The Shmutz

RS: How do you start these new paintings?

JB: There’s a long period of just groping around. I usually have some kind of source material to work off of—a drawing or a found image—but this ends up getting buried in the process. Most of the painting happens on the floor, then I’ll pin them up periodically to see what they look like on the wall. I work on both sides of the painting, too. If one side starts to feel unmanageable, I’ll turn it over and screw around with the other side. That was something that just happened out of being a frugal guy, I guess. But then, because I am working on unprepared canvas, I get this bleedthough. The oil paint will bleed though to the other side, so I get this sort of incidental mark.

RS: Is that a lot of what you see here? Is the incidental mark?

JB: Yeah, I mean, I could point it out. Like on this one [pointing], that kind of pinkish triangle to the left is bled through.

RS: The purpose of priming a canvas is to prevent it from doing that, from…

JB: Rotting.

RS: Is that a worry of yours?

JB: I don’t lose any sleep over it. As long as they’re OK during my lifetime. Maybe someone else will have to deal with it.

RS: Do you just like the look of raw canvas?

JB: I like the way it looks, and it feels more like drawing to me. The raw canvas looks like paper to me. Like newsprint. With a primed, gessoed canvas I feel compelled to fill the whole thing in. You lose some of the drawing…

RS: There’s also just this atmosphere of—

JB: Shmutz.

RS: Do you let this shmutz dictate what you paint? Do

you riff off of accidents?

JB: The shmutz—the accidents are important. There’s not a lot of really direct drawing in these things.

RS: “Direct drawing” meaning you have an idea and then you try to make that idea?

JB: Yeah, it’s more about conjuring something over time, rather than having… you know, thinking, Oh I’d like to draw a pony here, and then just going for it. And living with it.

RS: Do you think about these new works as pure abstraction?

JB: No, no. I don’t think of these as abstract paintings.

RS: So they’re figurative, to you?

JB: I mean, I can just pick out, you know, a face, a bald head, a beard, and then a sort of hand with a finger pointing down. And over here we have, like, a sort of purple head regarding this guy with a blue cock, and then a sort of hawk nose, you know? [Laughter] That’s just, uh, yeah…

RS: I think it’s great to hear you say it bluntly like that. The language is pretty dumb-sounding, but the image “guy with a hawk nose” can become something magical.

JB: Hawk nose…

RS: Do you think when you look at other people’s abstract paintings you can also see figuration in there?

JB: It’s hard not to. You know, you look at a Rothko: there’s the cloud and the horizon line, the ocean… it’s hard not to pick these things out.

RS: “Pareidolia,” it’s called.

JB: It’s a disease? A syndrome?

RS: You got a problem, man… [Laughs] No, it’s the phenomenon of seeing, for instance, the man in the moon, or faces in clouds. But I think it can work with anything. This wall here—

JB: No, I think I might be afflicted.

RS: Sometimes when I’m looking at art, especially abstract stuff, I notice my eyes feel different, foggier. Ever notice that?

JB: Oh, yeah. I have noticed that. When I’m looking at a painting, my own painting or anyone’s. You enter into a kind of light trance. It’s strange. Your eyes glaze over a little. There’s a subtle shift in consciousness.

RS: How many hours a day are you in the studio?

JB: It depends. I just come in as much as I can. I’ll go through a concentrated period of painting, and then I’ll take a month off, or something like that. I don’t want to treat painting like a job, and I don’t have any assistants, so no one is expecting me to show up.

RS: When you make art now, does it feel like it did when you were drawing as a kid?

JB: No. When you’re a kid it just comes naturally. It’s just for fun. As an adult it’s just, y’know, more involved. I have adult responsibilities. You read the paper, and all this kind of shit, and it ends up making it a dire situation. It’s not just play.

RS: Did you go through a period where your drawing was a lot more refined and controlled?

JB: Well, in school I learned to draw from life. Figure drawing.

RS: Were you good at that?

JB: I was OK. I’m a pretty decent draftsman. But… there’s this sort of skill purgatory that most of us are in. I can’t draw like a child, and I can’t draw like Rembrandt. I’m in the inbetween. You reach a certain skill level, and then you just work with your limitations. If I just sit down and make a natural drawing, it looks like something one of those guys on the boardwalk would draw. You’d be riding a skateboard with a huge head…

RS: You had a career laid out in front of you.

JB: You could do worse.

III. Dicks and Swastikas

RS: I saw a show of yours, not so long ago, at the Journal Gallery. It was all these very small scrawled drawings. And it seemed like the other end of the spectrum from the monochromes, like you’re just displaying this totally mindless kind of art, right?

JB: Yeah, those drawings happened not in the studio but kind of around the kitchen table. They’re more like doodles than finished, beautiful works on paper.

RS: Right, but you still show them as if they are. I mean, you present them in a nice frame.

JB: I just had this backlog of stuff sitting around. I kept trying to draw in the studio, and it always ended up feeling a little forced. Finally I thought, Why don’t I just show this stuff I’m making that seems to be happening kind of naturally?

RS: Would you place these little doodles alongside your paintings? Or are they something different?

JB: Well, drawing is so direct. You can make a drawing in a minute, or thirty seconds. With drawing, the stakes are so low. It’s a good place to generate material. If it’s no good, you just throw it out and move on to the next one. The paintings I kind of suffer over, but the drawings… it’s easy. Sometimes I’ll get on a roll and make ten or fifteen good drawings in an hour. It’s a good warm-up for painting. I don’t sweat them. But the paintings are taking longer and longer to make.

RS: How long?

JB: A few months. I’ll typically work on a group of paintings, maybe ten at a time. I’ll work in spurts and just look for a while. The idea is to end up with something that is unrecognizable. I don’t like to look at a painting and be able to retrace the steps.

RS: Sometimes I’ll draw on the subway, or in the car, so I get a nice, jerky mark I wouldn’t have made without something external messing up my intention

JB: Yeah, there are all sorts of ways to glitch the system, to break your own patterns. I just saw a photo of de Kooning drawing with his eyes closed. He made all of those great little drawings in the ’60s and ’70s with his eyes closed.

RS: De Kooning seems like he makes drawing with his eyes closed and then go back over it to pulls something out of it. Whereas Cy Twombly just makes the mark and leaves it nasty and sloppy.

JB: I just love Twombly. You see a Twombly painting today, and it still looks so fresh. It’s like bathroom-stall art.

RS: Is that something that resonates with you—bathroom art?

JB: Yeah. I like to see what someone who doesn’t draw does draw when they draw. It’s always the same stuff. Dicks and swastikas. I’ve been paying attention to graffiti, too—tags and that sort of thing. It’s funny. It’s just visual background noise until you start to engage with it, and then you just realize that it’s everywhere.

RS: Or even the collages people make by tearing up advertisements in the subway. Once you pay attention to that and really look at them, it’s more exciting than a lot of work in galleries.

JB: If someone says, “Here’s a wall, do whatever you want, the cops aren’t going to come,” then it’s always a piece of shit. It’s just terrible. I like it when they have forty seconds to throw it up.

IV. Art at the DMV

RS: How do all the accidental marks—the shmutz—on your paintings happen?

JB: I work on them flat. I walk on them. They pick up paint and whatever else is on the floor. I like them to look really filthy.

RS: There’s a sort of philosophy in filthiness, right? Like

if you’re letting the work be messy, you’re accepting messiness rather than fighting against it.

JB: I suppose, yeah, it reflects the mess that we’re in.

RS: I wasn’t really thinking, like, political overtones…

JB: Well, let me tell you, these are political paintings!

[Laughs]

RS: At the same time, you maybe aren’t very controlling, but you do sweat over these paintings.

JB: I think these are well-crafted paintings, you know. Craft is just attention to detail. A well-crafted painting doesn’t have to look… Like, Ellsworth Kelly is a great craftsman, and you can see it. It’s obvious because the paintings are so pristine, so beautifully finished, but Twombly was a great craftsman, too. Even though he was smearing shit.

RS: Maybe you’re not drawing dicks everywhere in your paintings, but on some level you’re still trying to get that same kind of impulse.

JB: Yeah. The regression thing keeps coming up with my work and… I’m not even sure if I’d argue.

RS: When you say “regression,” what do you mean by that?

JB: Well, I guess the straight idea… I don’t know. Avoiding adult responsibility and adult themes? Engaging in base primitive behavior?

RS: Can you point to some regressive artists?

JB: Picasso, Pollock, Dubuffet… I mean, the whole enterprise— art-making in general—would probably be considered regressive, frivolous behavior. We should probably all be working on some new kind of bomb! Something respectable.

RS: What sort of stuff outside of the conversation gives you your visual kicks?

JB: Just anything—anything that’s around. Record covers, comics, illustration.

RS: Do you look at much outsider art?

JB: I do, yeah. William Hawkins—I think William Hawkins was a great painter. I was at the DMV recently, and there was this fucking great painting on the wall by somebody. It was not charming like folk art or children’s art. It’s what I’ve been looking for recently. Teenage art, I guess it is. Just bad drawing.

RS: Where else would you find this kind of work?

JB: I look for it. I mean, I could show you some examples— a friend just gave me a great book that’s just all these Xeroxed punk-rock flyers, and there’s a lot of it in there, some seventeen-year-old kid drawing a guy on a skateboard with a Mohawk. I remember being very taken with punks. With the way they looked.

RS: Were you a punk-rock kid?

JB: Yeah, I was interested in punk rock when I was a kid.

RS: I was interested in punk rock.

JB: [Laughs] It was an interest of mine… Were you?

RS: Yeah.

JB: As you can see, there’s a lot of source material here. I can’t paint all the time, and I’m here a lot, and I can’t draw all the time, so I look at books. There’s an absurd amount of time spent just looking.

RS: What would you say is the ratio of looking to actually painting, in the studio?

JB: It’s embarrassing. Maybe ten to one.

RS: Which of your paintings have you loved most?

JB: The ones that I really love the most are the ones that made me deeply uncomfortable to begin with. When I’m working on a group of paintings, there will be one or two that appear to be ahead of the rest, and then there are one or two that seem hopeless. These hopeless ones always wind up being the best, because you don’t really care about them. You can push them over the edge.

RS: Their badness becomes an asset.

JB: That sounds about right. If you look at art all the time, after a while you just get burned out on the good stuff, and then you have nowhere to go but down. That’s where I’m looking. The stuff that’s really been turning me on these days is—I guess you’d just call it “café art.” It’s usually a painting of someone playing a saxophone. Like that. I love the idea of making a show that is just unacceptable. Something so bad that I would have to leave town.

Published by The Believer in 2014