An interview with Gladys Nilsson

"Things just keep blossoming. It doesn’t stop."

Ross Simonini: I’ve read that all your work starts with drawing.

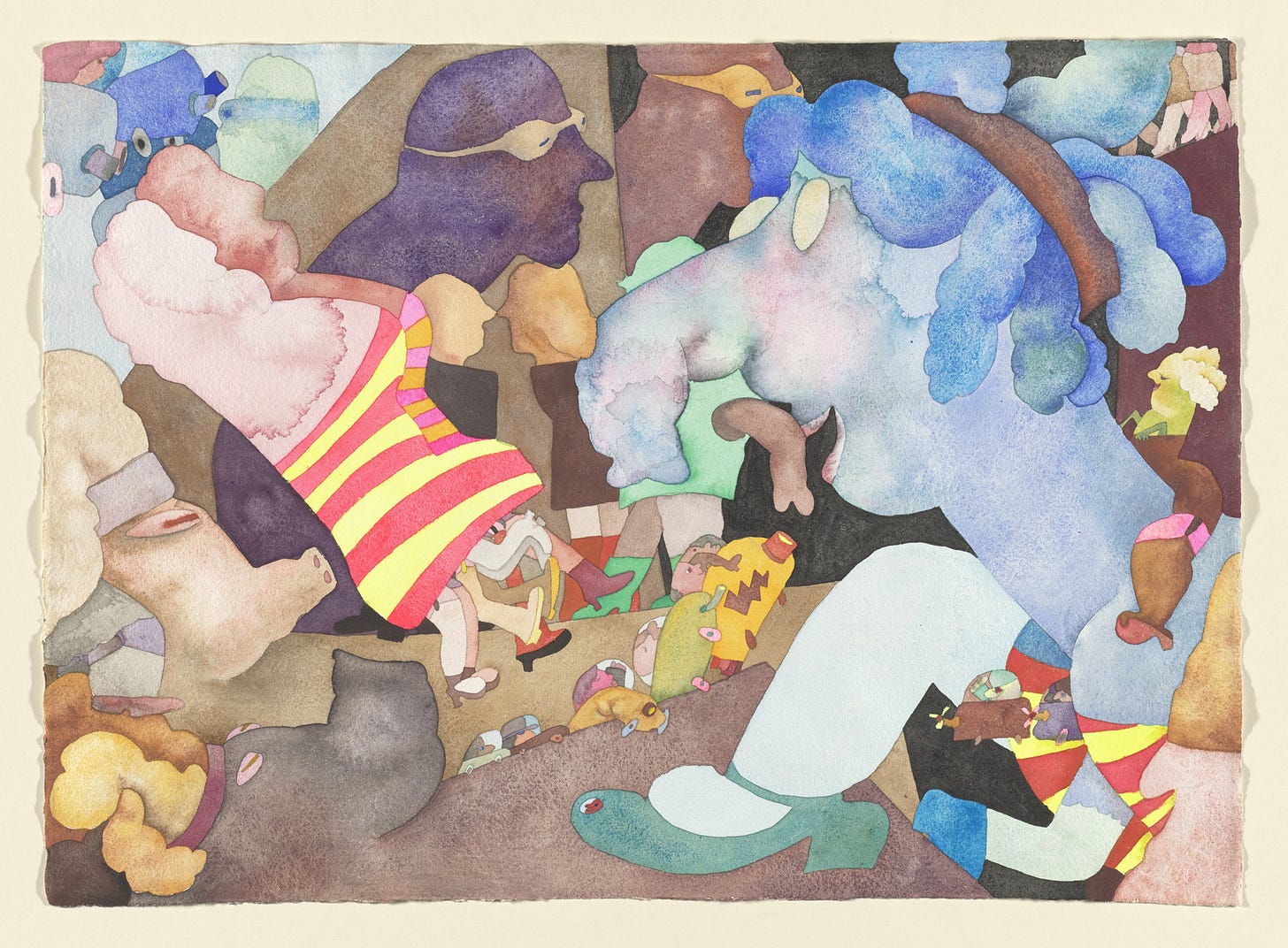

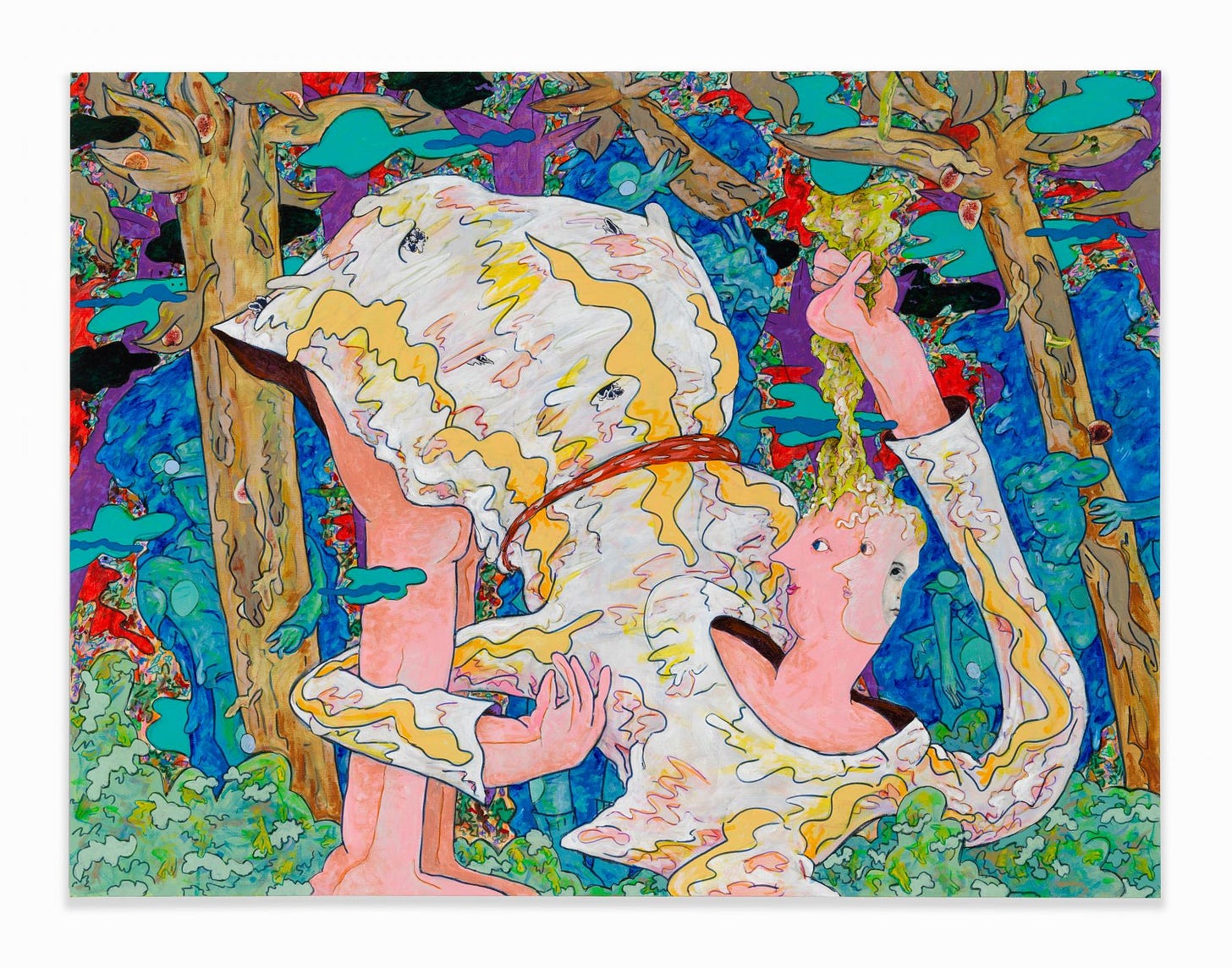

Gladys Nilsson: Yes, since my primary medium is on paper, using paper as the support vehicle. I do a drawing underneath the watercolor. Most of them are watercolor on paper, although from time to time I segue into a different kind of material used, but typically it’s watercolor on paper. So yes, underneath a watercolor has been formed and shaped and erased and redrawn until I arrive at exactly the image that I want to use, and then I start thinking about, concentrating on the color and the paint application. It’s two different steps. I don’t draw and then paint, draw and then paint, like maybe one might do with something else. My method is to get the drawing set, and then concentrate on the color application.

RS: And when you’re making the drawings, are you telling yourself stories about what the drawings are depicting?

GN: Yeah, there is a narrative that normally goes through it. As I’ve been getting older, I’ve been thinking back, reflecting more and more on my childhood growing up, what kinds of things I was seeing at that point. I can remember certain get-togethers where the women would be doing one thing over here and the men would be doing another thing. Just the kind of dynamics in that social group. Me and my cousins were first-generation Americans in a reasonably big family. All of the adults in the family were immigrants from Sweden. They were very much Old World, having come here from the ’20s and ’30s. It still was an Old World Europe transforming where they lived and how they lived here in America. So it really is basically thinking back on certain things that are very vivid in my mind with the women in the family, who were all very strong, very silent, and who I admire, more now than I did as a child, of course. Children don’t admire much.

RS: Was this in Chicago?

GN: No, they lived in the southwestern part of the state over near the Mississippi. So for whatever reason, all of that family, my family, aunts and cousins and uncles, there was a huge migration that went on in the ’20s and the ’30s to settle along that area. And then my mom and dad managed to meet in Chicago because my mom got a job working in Chicago, and they met at the Swedish Club. Since my mom’s family was in this other area, we would visit quite a bit when I was a child.

RS: Is Swedish heritage something that figures much into your life and art?

GN: Not really. It just is a fact of what was. I don’t really think about it. It doesn’t really have any direct bearing, I don’t think. My work doesn’t look like it came out of Ingmar Bergman movies. It’s something I haven’t really incorporated. Although for a while in the early 2000s, I really started thinking about immigration. My parents passed away, not at the same time, but along in the early 2000s, so I got all of these old family photos, and realized that any immigrant that takes this giant leap of faith from what they’re used to—and leaping into the New Land, and the New Land was a lot tougher than now, although there is still toughness involved—I just started thinking about how they came over on a boat, went over to Ellis Island, which was at that time very difficult, I have no idea how difficult it is now, but just the whole general idea of immigration of any person. I did a series of things based on that idea.

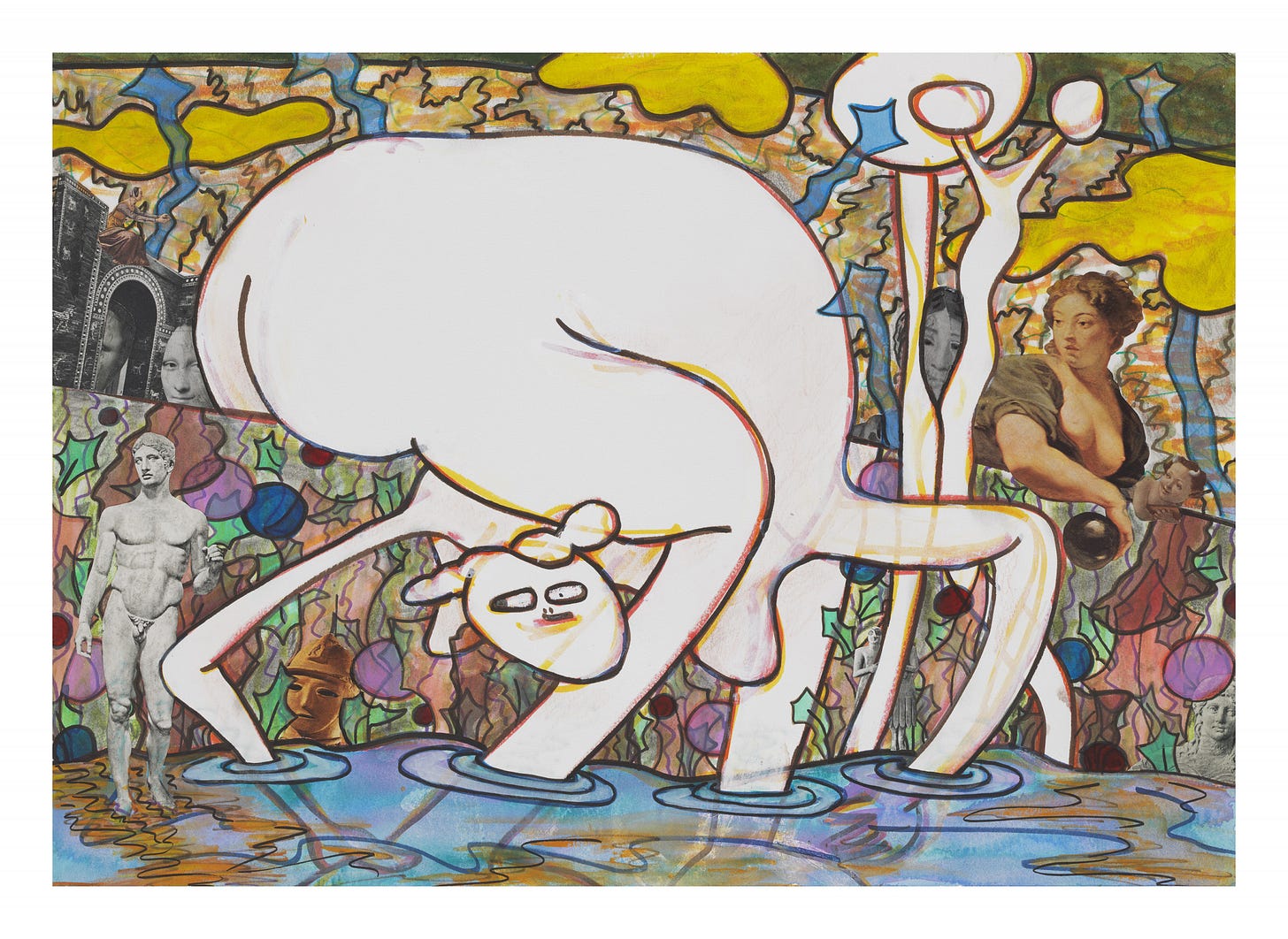

RS: Do you use source materials for your work?

GN: Yeah. I have huge amounts of art books. Currently, I’m working on a series of things that have been using atypical drawing and a lot of collage work. The collage work I’m getting out of an old, a long time–unused art history book and art books that I’m clipping out, so a lot of things are based on historical images. I also have a wall of photographs that I have some old family things on, and a lot of times I look directly across at grandparents and great-grandparents in their poses. So there is a combination of a certain kind of antiquity whether it goes back a long ways or is just back around the turn of the century. I mean the previous century. (Can’t say that anymore and have people know what you mean.) But they all reference classical paintings from fifteen-something, or Greek statuary, bits and pieces of art history, that are blasphemous, actually—cutting apart these art history books that one respects and reveres.

RS: Is it because you especially enjoy that classical work?

GN: Oh, I like it. It’s great fun. And for me, fun is good. If you aren’t having any fun doing something, then why bother?

RS: In general, do you think making art is fun?

GN: Yeah. I like what I do, I get a great deal of satisfaction, like in the collage work, out of finding the exact image that’s needed in a specific place to complete the idea of the drawing. When I’m doing my watercolors, I get a great deal of satisfaction out of the manipulation of the paint. I know exactly what I want to do and how to do it. And after you do it, it’s just very pleasing.

RS: Do you have much relationship with illustration?

GN: No. Not at all.

RS: What about abstraction?

GN: Well, there are some things that happen in areas of colors that can be very abstract, and I think that holds true with a lot of painters no matter how far back you go. I was walking through the museum of the Art Institute the other day with someone, and we were looking at work and looking at certain aspects of Rubens that we were pondering in the museum, looking at just passages, not just images but you come up and you look at passages and how paint was applied, and the same holds true if you look at Sargent watercolors—how pigments and brushstrokes work can be very abstract, and you pull back further and it comes together in an image. So there is a kind of quirky quality that paint surfaces can have.

RS: You were quick to say no to illustration. Is that something you feel strongly about?

GN: Yes. I will admit there is a certain narrative quality, but not all narrative work is called illustrational. I don’t think about illustrations. I don’t read books with illustrations anymore. When I was growing up, there was See Dick Run and See Spot. It’s a specific look that not all figurative and narrative work has. Since I don’t think about it, I don’t know. That’s the touchy point between art and craft. And that’s a very touchy point. Are people who work with clay and ceramics craftspeople or artists or artisans? There are a lot of touchy fine lines that you waste a lot of time thinking about. I’d rather waste my time cutting up things with my books than thinking about nomenclature.

RS: Do you ever waste time?

GN: Pardon me?

RS: Do you feel you waste very much time?

GN: No, no! I don’t waste very much time at all. That’s why I just said, I don’t want to waste my time thinking about that kind of definition or descriptive feeling. I’d rather do something else.

RS: Do you read much?

GN: Yeah, I do, I do. I read mystery thrillers, fiction. I don’t read much nonfiction. I read fiction a lot. I never shortchanged reading time, which is generally after breakfast, after lunch, on trains riding downtown, and so on. Very valuable time. You get a lot done just sitting on a train, reading.

RS: Yeah. You live in the suburbs, right?

GN: Yeah, Wilmette. Northern suburb of Chicago.

RS: Has that affected you much?

GN: No, because by the time we moved here, even though we’ve been here thirty-nine years, my work was, in terms of sense of personal direction, very formed, so that there was just development of imagery. The suburbs offer you quiet when you want quiet.

RS: At what age did your work solidify?

GN: I think it solidified pretty much in the early to mid-’60s. And that was really development of what materials one is using, and how one is shaping and forming the drawing path. But the imagery and the kind of imagery and the interest of imagery and the kind of invention of scenario that I like in my work, [that] was already there at that point.

RS: How would you describe that imagery?

GN: What do you mean, how would I describe it? You mean the difference between a 1966 watercolor and a 2012 watercolor?

RS: Yeah.

GN: Well, the drawing and the invention of figures is more refined. Figures are a little bit more gentle than they were, I think, whenever that may have happened. But they were pretty blocky, maybe, cruder, not drawn with as much finesse as I tend to draw now.

RS: Would you say you’ve been working to depict a certain world, or a certain place at all?

GN: Yeah, I think so. No matter what or how it might shift and change in terms of locale—are you inside a room or outside a room, does the room just disappear and just become one big shape? I think it is a continuing involvement of a world that is my own.

RS: And are you still teaching?

GN: Yeah, I still teach one class in drawing, a multimedia works on paper class at the School of the Art Institute. I really like seeing this solving of problems that students do when you give them the same situation of things to do, over the course of, say, twenty years, and they are basically approaching it [in] the same manner as someone did twenty years ago, and students here are very similar to the students in another state, and so on. It’s a certain (and I’m sure when I was a student it was the same kind of thing) searching and moving through certain material and ideas and things. Forming yourself.

RS: Do you have any sort of philosophy of teaching?

GN: It deals more with personal invention and use of various materials and exploration that perhaps they wouldn’t have the chance to do in another class.

RS: You started off teaching children, right?

GN: Yes, very early on in the early ’60s. I had a class at the Hyde Park Art Center. I can’t even remember if it was a painting class or a drawing class. They had materials and they did stuff. It was on a Saturday, a typical children’s class at the time. Children of a certain age are absolutely fearless in terms of doing stuff and in terms of how freely they put marks on the paper. Then their parents interfere and say, “That’s not nice, you should draw a tree like this,” and begin to interfere with certain creative processes that most children have naturally all along, so it’s kind of interesting to see both things happening, and then trying to keep a certain freedom alive in terms of what kids are doing. There was a lot of thought, when I did some pickup teaching work in Sacramento when we lived out there in the college. I began to think that the kids were more interesting at the Hyde Park Art Center than they were by the time they reached college, in terms of expressing themselves, if you know what I mean.

RS: Would you say that childlike approach to art has at all made its way into the way you work?

GN: Well, children’s art in general, there’s a certain interesting thing about it, or about naive or untrained art. There’s a need to put something down regardless of if you actually know how to draw something—that part is very interesting to me, that the vast desire to put down a thought is more important than the skill level that one might think is needed, that it’s the emotional connection that’s most important.

RS: I read that you and your husband (the artist Jim Nutt) rarely talk about your work with each other.

GN: We’ve been married coming up on fifty-three years now, and we’re probably still together because we don’t talk about each other’s work. We admire each other’s work—that’s a given, that we really like each other’s work. We just don’t voice it, other than, “Oh, I like that.” That kind of thing. And that kind of surprised a lot of people—a number of artists in Chicago. We didn’t sit around and discuss art. We might say, “Oh, I saw this great show at a museum or gallery,” and maybe say why we liked it and recommend to go and see it, and then proceed on to other things.

RS: Is that because in general you’re not someone who likes to sit around and talk about art?

GN: Yeah, exactly.

RS: As you said earlier, you said you think it’s a waste of time to philosophize about it.

GN: It’s just something that really doesn’t interest me. I’d rather say, “Well, I saw a really great play and it was just really interesting how these things get put together,” rather than to say, “Well, I’m working on this and that, and so-and-so is working on this and that, and we should talk about how great meanings of life are, in terms of art.” I mean that’s too deep, that’s not any fun. It all goes back to fun, you know. You gotta have fun.

RS: You mentioned Chicago artists. Did you feel very connected to the Hairy Who as a group?

GN: Oh, we were very connected. We didn’t sit around and talk about our work, but we ended up being very connected, and we still are. Each one’s work interests the other, and we go about our business and see each other once in a while and catch up on stuff, but we are connected. It wasn’t just press forming—well, names of the general overall Chicago Imagists wasn’t anything we thought up. I don’t think any artist or any group, unless they themselves call themselves something, comes up with the name of what they are.

RS: Would you say having children affected your work in any particular way?

GN: No, not really. I was always very focused in terms of…well, what I had to do was just figure out the time frame in being able to do what I needed to do to proceed in the studio. I wasn’t going to give anything up studio-wise. I have a very, very strong sense of direction. My sight lines are straight ahead. I’m very strong that way.

RS: You didn’t slow down.

GN: In terms of the studio and creativity. There’s nothing that I’m giving up. The older you get…I think when you begin to ponder any creative person who is older, whether you’re a musician, composer, writer, artist, dancers—well, dancers are limited to physical, but then they go on to, maybe, choreography, and so on—most of any creative being’s most exalted work happens when they get older. They keep growing. Things just keep blossoming. It doesn’t stop. Well, maybe some things do. But generally it just keeps moving, and great things happen.

Born in Chicago in 1940, Gladys Nilsson studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She first came to prominence in 1966, when she joined five other recent Art Institute graduates (Jim Falconer, Art Green, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum) for the first of a series of group exhibitions called the Hairy Who. In 1973, she became one of the first women to have a solo-exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In 1990, she accepted a teaching position at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she is now a professor. Nilsson is known for her densely layered and meticulously constructed watercolors and collages. Like many of the Hairy Who artists, Nilsson employed a type of horror vacui; many of her works feel filled to the brim with winding, playful imagery. Her work often focuses on aspects of human sexuality and its inherent contradictions. Since 1966, Nilsson’s work has been the subject of over 50 solo exhibitions.

A few other recent publications:

An episode of Subject Object Verb with artist, Ei Arakawa on music as memory

An interview with musician, Pat Metheney for The Believer Magazine