An Interview with Carroll Dunham

“When I Started, I Wanted to Make Paintings That Any Idiot Could Make. You Didn’t Need ‘Talent’ to Make These Paintings. You Just Had to Think in a Certain Way.”

The world of Carroll Dunham’s art is a faraway place, deep in the unconscious, where perennial myths and night terrors are born. His painted images go straight through the eyes, back to that lizard part of our brain—violence, sex, genitals, color.

Dunham spends years cultivating small plots of his world, developing each glyph of his visual language with the sort of long-term, exploratory scope that a science-fiction novelist might use. Early on, he spent a decade painting in a pool of hallucinatory, anatomical abstraction, growing organs and biomorphic shapes individually, until little angry faces and fat bodies began to sprout. Eventually, an anthropomorphized sun was born, a tree, a mountain—all the basic building blocks of any world.

Over the next decade, he built an electric, masculine dystopia. Its primary inhabitants were menacing, eyeless, penis-nosed men, with gritting teeth, wearing suits and stovetop hats. Through hundreds of drawings, prints, paintings, and sculptures, Dunham compulsively re-created these figures from various angles and positions, sometimes in a vast, barren wasteland, or in a cabin, or with guns, until the world seemed to have been comprehensively mapped.

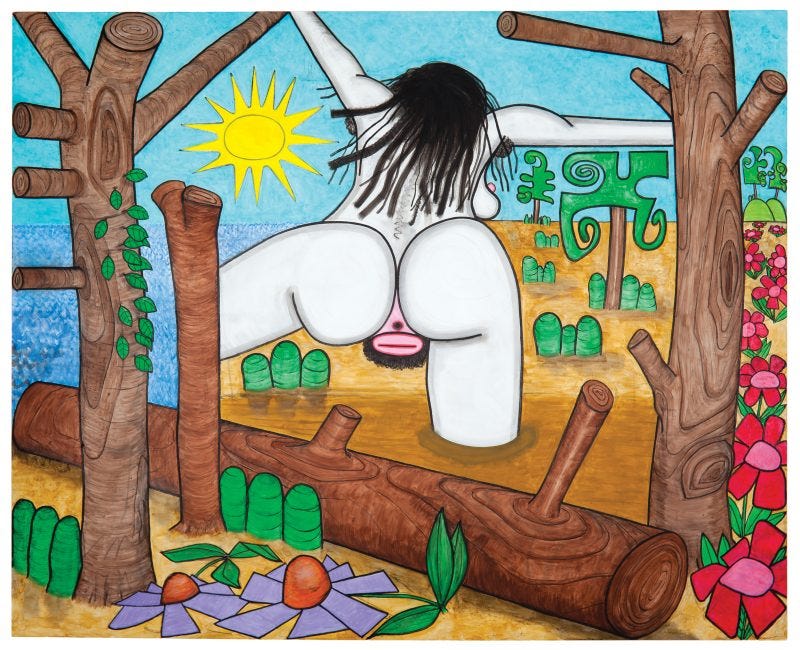

Since 2010, Dunham has begun working in another territory: the heaven to the previous decade’s hell, a paradisiacal, feminine land with large, flapping flower petals, abundant foliage, blue skies, and rolling hills. Here lives a nude, pink-skinned woman who is forever diving into pristine water, her anus and vulva and black hair aimed at the painting’s beholder, as if we were a newborn projecting from her womb.

And yet for Dunham, these subjects, so bold and direct, are not his primary concern. Figures and scenes are just the skeletons on which he can drape skin in a seemingly infinite number of arrangements, the way a blues musician uses the blues, or a poet occupies a sonnet. Through these standard forms—the nude, the cartoon, the landscape—Dunham can transform abstract thought into worldly shape.

For the following conversation, Dunham and I met at his gallery, Gladstone, in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York, where an exhibition of his recent “Bather” paintings was hanging. Dunham is a reader, and, in addition to art, we discussed the books of Philip K. Dick, Wilhelm Reich, Frank Herbert, and Carl Jung.

—Ross Simonini

I. HOW I MAKE MYSELF SEE THINGS

ROSS SIMONINI: Are you interested in creating a particular experience through your paintings?

CARROLL DUNHAM: I have a deep, deep love of painting. I mean, I’m really pretty hooked on it. That isn’t to say I’m having a blast every day, you know. I mean, it isn’t like that, but I think, at this point, I can see that all the different things I might feel about painting are starting to assert themselves more simultaneously. I would like to think that what I’m doing now is a rich visual experience and has the possibility to—I don’t want to use words like transport you, but, I mean, maybe you can kind of go someplace else for a while when you look at [my paintings]. But for me, making them, all I can really know is what’s happening for me. Probably the reason I speak about this in such a detached way is because I don’t really want to make claims for them. I can’t tell you what to see. To me it’s kind of straightforward: on one level the subjects of those paintings are idiotically clear, so in a way that whole thing of “What do they mean?” is neutralized. You know, you can’t tell me that you don’t recognize these images.

RS: The images are almost archetypes. The subjects are not someone in particular—they’re broader than that, like folk art.

CD: Well, I would love to think that. I mean, I’m not dealing with specific personalities as subjects. It is much more like what you just said, for me. I think of things more structurally than I do topically. I’m sort of a closet Jungian.

RS: Why’s that?

CD: Jung’s whole model of the psyche is something that I’m consistently and thoroughly in agreement with. The idea of archetypes as things that have their own agenda— that are operating in human language and human visual culture—I think is clearly true. I mean, it’s not completely unrelated to the idea of the meme in its original usage (not in the way it’s now used, as an internet thing). But there are things that language seems to want and there are things that visual culture seems to want that seem to be almost independent of any particular artists or writers.

RS: Or of any particular culture.

CD: Exactly, exactly. I don’t have a consistent theory of the world, but I do feel strongly that this is going on.

RS: There are these underlying symbols.

CD: Yes, and I feel that I kind of put myself in the service of painting, and that’s what I’m doing here, that’s how I’m channeling, you know, whatever. Maybe it’s all just random neurons firing in my brain, but it doesn’t feel like that.

RS: Do you read about this kind of thing?

CD: I read a lot. I read all the time, and my reading ranges from science fiction to philosophy I can’t even understand. Right now I’m reading the last three books that Philip K. Dick wrote. I’ve been reading science fiction since I was a kid, and I made one pass at Philip K. Dick back in the day, but it wasn’t my thing. I was much more interested in people like Frank Herbert.

RS: Do you tell yourself narratives about what you’re painting?

CD: Well, it’s really interesting that you ask that. There was a time starting around, I don’t know, the late ’90s, when my work started to be dominated by this male character that came out of my drawing and it stayed around in different ways. I was reading a lot of Wilhelm Reich back then; I was getting interested in the idea of nutty science and Reich somehow was the person I was drawn to. I really liked his ideas about sexuality and this idea that he had discovered a heretofore-unknown form of energy in the universe (orgone), and it seemed like it had a lot of metaphorical possibilities for paintings. I was writing in my journals and I came up with this idea of something that I called “the Search for Orgone,” and I realized that this character that I kept drawing over and over again—he seemed to be appearing in these highly abstracted landscapes and never went beyond this profile, this shoulders-and-head profile of a character embedded in these different landscapes. The body of work became subsumed under this idea of “the Search for Orgone,” and I wrote a lot of stuff in my journal about it. I tried to see if there was some way I could generate an actual story, but I couldn’t. It just doesn’t seem to be how my writing lets itself out.

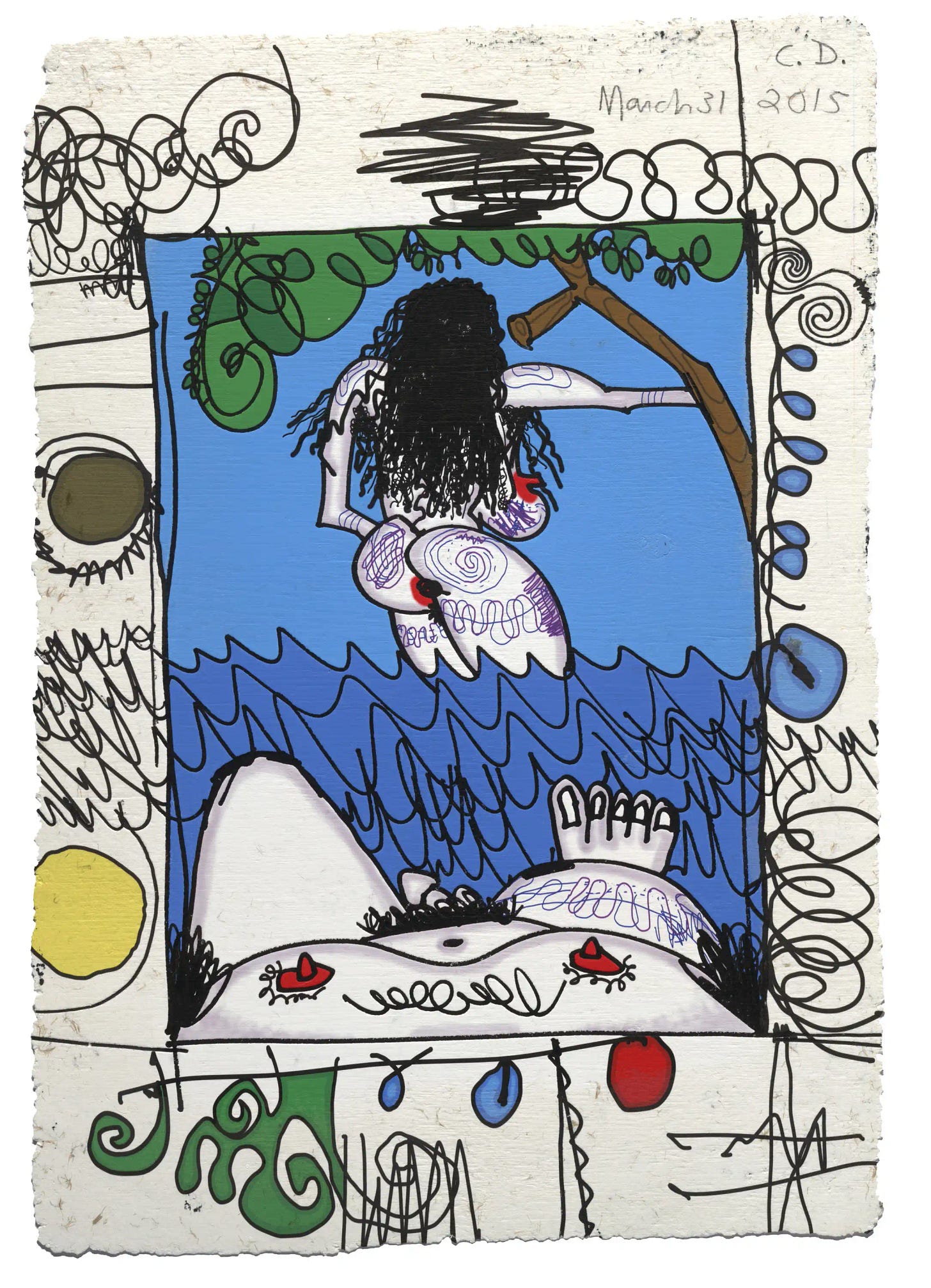

RS: You date each painting very carefully, including the breaks in between paintings, right on the canvas. Why is it important to you to have the time line in the painting?

CD: It’s so I can see when I made something. I guess there’s something basic to the meaning of what I do that to me involves the chronological order in which things occur, sort of how the experience unfolds for me. I have always dated my paintings, and it just feels right. I want information to be on the surface of the painting, not hidden on the back. And I date all my drawings. I don’t date the paintings by day; I date them by groups of months when I work on them, which seems to be enough for me to know down the road.

RS: What are you trying to learn from doing this?

CD: I can’t exactly say, except that the order in which one’s life unfolds seems very key to what it is. It’s part of the art, and a signature to me is just a kind of ritualized form of acknowledging completion. I sign things when I feel that I really know that whatever transfer was meant to happen has occurred.

II. BURROWING

RS: Early on, you painted on objects, on walls, on lamps.

CD: Originally, I was painting on the walls of my studio or of my apartment. I started to want to change that when I was moving around, and it was just too difficult to keep a train of thought going. It had a lot to do with what the atmosphere was, the way the conversation was going in the art world. Around that time—when I first came to [New York]—I was working for artists, and I helped people make installations that involved making marks on the wall or painting on the wall, what we would now call site-specific sculptures or installation-type stuff, so it was in the conversation that I was becoming involved with that things should occur somehow on or in the architecture rather than as separate objects.

RS: At that time painting on canvas was pretty unfashionable. Was it a response to that?

CD: Well, you know that “painting is dead” thing—it seems to be this kind of massive tic. People just keep trotting that out. It’s ultimately just some kind of rhetorical device. I worked for artists who didn’t make paintings, at least in the traditional sense of the term, but they were extremely interested in the history of painting. I knew a lot of people who were thinking about the history of painting. I just didn’t know a lot of people who were making portable, flat, four-sided paintings. So for me it was important to set myself away a little bit from the artists I had been around, influenced by, talking to, and also I just needed emotionally to settle on something and just say to myself, Well, this is what I do. I just needed that. And that came at the same time as I was realizing I couldn’t just keep moving from tenement apartment to tenement apartment, putting crap on the walls of these apartments—it all kind of consolidated into this idea of: I’m just going to do this because it’s a territory I can inhabit somehow. I had a feeling about it.

RS: You were coming to tradition from the back end.

CD: I actually think that’s a perfect way to put it. As soon as I did that, everything was good. I mean, not good, but I could go forward. I could see a way to work.

RS: You had a project.

CD: I had a project, exactly.

RS: You worked with Mel Bochner, who is known for his expanded sense of painting.

CD: Well, he’s an old friend of mine, and I met him when I worked for another artist, named Dorothea Rockburne. They were friends. I was twenty-two, twenty-three years old, but I was around, and Mel and I just became friends. I did help him as his assistant with some exhibition installations, which was a very important experience for me in terms of thinking about how I wanted to work. And, you know, that was painting on the wall. Mel was making these really amazing things painted right on the wall. In the beginning I saw myself as trying to operate in a similar way, but then, you know, you find your own thing.

RS: I’ve heard you say that you arrived at painting from a philosophical position.

CD: I did. I mean [pause], it’s odd when I think about what my paintings look like now, but of course I can see all the connections back to all that. When I told myself I was going to make paintings, it was pretty clear to me that there weren’t very many people making paintings that I was interested in. I was very interested in Robert Ryman. I was very interested in what Brice Marden was doing at the time. Agnes Martin. Robert Mangold. Those were the kind of people who were making what you could really call paintings, who were in a conversation that made sense to me. So I think for my friends and me in the early ’70s, everything had to do with figuring out what to do after artists like that had basically, in a way, almost zeroed everything out.

RS: Yeah, those times.

CD: I think it was a dilemma for those artists, too. But they had a different problem living their lives than I had living mine. And my problem was how to kind of acknowledge these things as great and allow myself to absorb whatever they had for me without just coming up with some different riff on monochrome painting. And that took some time. I never thought that I would start painting landscapes and still lifes; I had no background in that. I saw painting as a philosophical exercise. Almost like you make paintings as a demonstration of something rather than as beautiful things. And that sort of demonstration model of painting was really what I came out of, and it still colors how I think about it.

RS: Is that about keeping a certain distance from the work?

CD: I have to be detached to make art. I do a lot of really small drawings that take no time and are very immediate and allow me to think about subjects in a really simple, fast way that eventually builds to be what can initiate paintings. But even at the level of doing really quick, almost diaristic drawings, I still think very structurally, and I think repetitively, almost like an obsessive-compulsive. I’ll have something in mind and I’ll draw it over and over and over, and then something mutates. That’s how I make myself see things.

RS: Would you say you’re thinking in terms of images or subjects?

CD: Much more in images and procedures. For example, if I’m just doing little pencil drawings, the thought comes differently than if I’m doing watercolors. It’s almost like the image comes to me if I think more about how to paint it than about what it is. So it isn’t like illustrating subjects; it doesn’t follow that vector of “it would be good to do a painting of a woman naked by herself in nature in the water.” It isn’t like that. It feels much more like burrowing through some tunnel. I see what the pictures are only once I’m into it.

III. SELF-TAUGHT NONSENSE

RS: You began as an abstract painter. Was that a choice?

CD: When I started thinking about painting, it was really clear to me that abstraction was the most important thing that had happened in the twentieth century and that, as the saying goes, it was “the art of my time” and that I wanted to get on that train. But what does that really mean, “abstraction”? Where is this line? Like on one side it’s alleged representation, and on the other side it’s alleged abstraction. I mean, it’s a very—it’s an asymptotic relationship. I’ve been making paintings—it’s been practically forty years, so my sense of my mission is highly diluted at this point. I realize more and more that I just want to keep doing my work. And I don’t even have the same picture of history now that I had when I started. I thought so much about this, but I don’t think I even believed a lot of the things I believed back then, in terms of where art—where painting—is supposed to be going, because I see myself as a medium rather than an agent. It’s so much about the imagination, and the imagination is so much about mystery, and as long as things keep occurring to me in paintings and I’m trying more and more to make the diagram, you know, my diagram, like, has to do with a highly selective vision of art history based on what gets me off, and it inevitably and miraculously leads right to my work.

RS: You said “back then” a few times. Was that like in your twenties and thirties?

CD: Yeah, it was part of realizing that I was really going to do this. I was going be an artist. And I had very clear ideas of what was OK and what wasn’t OK. It was pretty age appropriate. Now I feel less sure about knowing what’s good and what’s bad, which is actually a huge relief.

RS: The burden of carrying the lineage.

CD: Yeah, that’s taken care of without me. It’s like all I can really do is tend my own little patch here and try to make that as fully dimensional as I can.

RS: Do you have any particular painting technique?

CD: No one taught me how to make paintings. I mean, this idea that one is self-taught is nonsense. You don’t learn anything in art school. Everyone was self-taught, in terms of technical things.

RS: But you did go to art school.

CD: I actually went to normal college and got a degree in studio art, and believe me, at the time no one was teaching anybody anything. It was like reading art magazines, you know, doing projects. It wasn’t like any kind of rigorous studio work. I was always trying to find a kind of paint that will stand for paint, you know; a line that will stand for lines; support that would stand for support. It took me a long time to kind of evolve to the point where I just wanted to use painting on canvas. I’ve tried to take that basic drawing/demonstration/coloring-book thing and twist it and turn it in ways where it almost doesn’t appear to be that way anymore.

RS: It looks like you create the images with line drawings.

CD: Absolutely. What I’m trying more and more is I’m moving these big areas of paint around without lines around them and stuff, and trying to do more kind of almost like finger painting, shearing, but it all has to fit in this kind of matrix of structures. It’s another element in this vocabulary that ends up being all nested together. The “Bather” paintings happen much more on a flatter surface. They do come about just as you say: lots of work with drawing and lots of work with black-and-white paint and then, once the image is sufficiently built for me, I start to put color into it.

RS: Are these paintings built in layers?

CD: Yeah. That’s just part of what I’ve been trying to focus on for the last bit of time: the idea of no buildup in a physical sense but a lot of depth and density in an optical sense. If you look closely or see them under breaking light, you can still see the texture of the linen. I like the idea that the paintings might look like you have been seeing things through a translucent veil and then that veil is torn away. I kind of like that as a metaphor. Also there’s the expression “the veil was torn from my eyes,” which is meant to denote a deeper form of seeing. I find that a pleasing set of thoughts to have about painting. You have to embrace your limitations, you know.

RS: What were your limitations?

CD: Everybody has a style of thought. I think very graphically. I see things first and foremost in terms of lines, and my first instinct in any kind of attempt to draw anything is to get the outline. When I say limitations, I mean like accepting your style of thought. I think that’s what we mean when we talk about style.

IV. A PLAUSIBLE VERSION OF ADULTHOOD

RS: Do you research for painting?

CD: Yeah. I consider research everything from reading to going to museums to drawing to writing in a journal to going on a trip.

RS: And you do that more in those periods when you’re working on a show?

CD: Definitely, but I do it in a different spirit. It’s like, I know you’re trying to call to me, muse, and you’re breaking up, but you know if I go over here I’ll get your signal better. It’s the imagination, that’s the thing.

RS: In a Jungian-unconscious sort of way.

CD: Yeah. I heard Neil Jenney say something years ago on a panel that I’ll always remember. You know, Neil Jenney was part of the so-called “Bad Painting” group in the late ’70s, and then has gone on to do these precisely rendered paintings that are very different in a certain way from his early work but obviously connected. Asked about the evolution of his technique, he said something to the effect of that it would be really weird to do something all the time for years and years and not get better at it. Which I thought was a cool thought. He was just saying, My so-called technique is improving, but what kind of consciousness would I have if I’ve been doing something this much for this long and it didn’t change or grow in some sense?

RS: That’s different from getting better, though.

CD: Well, better is like the projection people have that there’s a standard. I think there is an idea of “better” in my own work in the sense that I want to be clearer if I can be.

RS: Is there anything purposely democratic about choosing a sort of coloring-book style?

CD: When I started, I wanted to make paintings that any idiot could make. You didn’t need “talent” to make these paintings. You just had to think in a certain way. Air quotes very much around “talent,” because it’s such weird concept.

RS: Has artistic success been pretty gradual for you? Do you feel like certain pockets of your work have been better received than others?

CD: It definitely confounds me. It’s not a comfortable thought for me to have to think of my life as a so-called career, because it just immediately becomes embarrassing and gross. You’re kind of chosen for it, on some level. It’s really interesting and it can also be really depressing and lonely. I feel lucky to have been able to do just this. You can tell that some things hit the people you know positively and other things don’t hit them so well, and you can read art reviews and magazines and realize that so-and-so thinks you’re a hack or you’re great, but it’s all hard. I think that you’d have to be an asshole to think that it all adds up to something you can actually get a picture of and think, This is the way I fit into the world and this is what people think about me. I mean, at what point do you feel you’ve got enough data to plot this whole thing out?

RS: Did you start working at a very young age?

CD: No, actually; I didn’t even realize that this was an inevitable course until I was probably about twenty-four or twenty-five. I always loved drawing. And I did a lot of, you know, hiding-out-in-the-dorm-room kind of drawing. But I couldn’t even imagine that it was a possible life for myself. I mean, I was aware there were people called artists; my parents knew a few of them. It wasn’t a totally impossible thought to have. I just never thought I could be one until I was really almost out of school and I started to meet older artists and they seemed to represent a plausible version of adulthood. I didn’t really start exhibiting in any kind of regular way until I was in my thirties.

RS: Were you resistant to it—to the commerce?

CD: No, no. Not at all. I just wasn’t organized. I wasn’t ready; my work wasn’t ready. The difficult thing is always the same and it’s still difficult, which is how you navigate, you know, this extremely private thing that comes from a private place and gets done alone in my studio, how it goes from that to all these other eyeballs. I still have trouble with that. You want so badly for someone to look at it and in a way it completes itself only if somebody looks at it. But at the same time that that completion occurs, you lose it. I’ve lost my painting. I walk around the gallery and I already know I’ve lost these paintings—even if I take them all back and put them in storage. There are a lot of people who have seen them and have ideas about them and have thoughts about them, and that’s no longer in my control.

RS: They’re swirled up with everything else.

CD: Exactly, swirled up with everything else. Nothing special. Just another bunch of things.

RS: It’s just part of visual language now.

CD: We didn’t invent the world the way it is. Like I didn’t come up with this cockeyed idea of art galleries and art collectors and art magazines. I didn’t invent this. I might wish all kinds of things about the way the world would be, but that’s not the way the world was when I came along. Just as some young artists now can’t control what they’re coming into. I’m quite prepared to make that trade-off. I guess that kind of goes to my idea about what painting is for. I accept painting. I accept it as a tradition, as a set of limitations, and within that anything goes, as far as I’m concerned. Anything that I can think of that I think would make an interesting painting is good. I mean, not “good,” but good with me.